Special Issue: Ethical implications of artificial intelligence (AI) and automation in service industries: Addressing algorithmic bias, opacity and unclear accountability mechanisms

Overview

Artificial intelligence (AI) and automation technologies are transforming service industries, including finance, healthcare, hospitality, retail, education, public services and digital platforms. While algorithmic decision-making systems, service robots, chatbots, predictive analytics and automated workflows offer enhanced efficiencies, personalization possibilities and scalability potential, these technologies are also raising profound ethical concerns related to their modus operandi and explainability of their outputs (Camilleri, 2024; Hu & Min, 2023).

As AI-driven service systems increasingly mediate interactions between organisations and their stakeholders; ethical failures and bias have the potential to reinforce existing social inequalities, undermine their trustworthiness, service quality, organisational legitimacy and broader societal well-being (Camilleri et al., 2024). Moreover, opaque “black-box” models reduce transparency and could erode user trust in these machine learning technologies (Kordzadeh & Ghasemaghaei, 2022). Unclear accountability structures may obscure responsibility for service failures or might facilitate unintended harmful outcomes (Novelli et al., 2024). These challenges are particularly evidenced in service contexts where human–AI interactions are frequent, relational and consequential.

Such concerns are clearly illustrated in healthcare services (Procter et al., 2023), where AI-driven diagnostic and triage systems are increasingly used to support clinical decision-making. When these technologies rely on biased or unrepresentative training data, they may systematically underdiagnose or misclassify specific demographic groups. Given the high-stakes and the relational nature of healthcare encounters, limited transparency and explainability can significantly diminish patient trust while raising serious ethical and accountability concerns.

Similar issues arise in financial and insurance services (Oke & Cavus, 2025), where automated credit scoring, loan approval and underwriting systems directly influence individuals’ financial inclusion and long-term economic prospects. Algorithmic opacity makes it difficult for customers to understand, question or contest adverse decisions. Therefore, biased models may perpetuate or amplify socioeconomic inequalities. Such an outcome is particularly problematic in service relationships characterised by long-term dependency and trust.

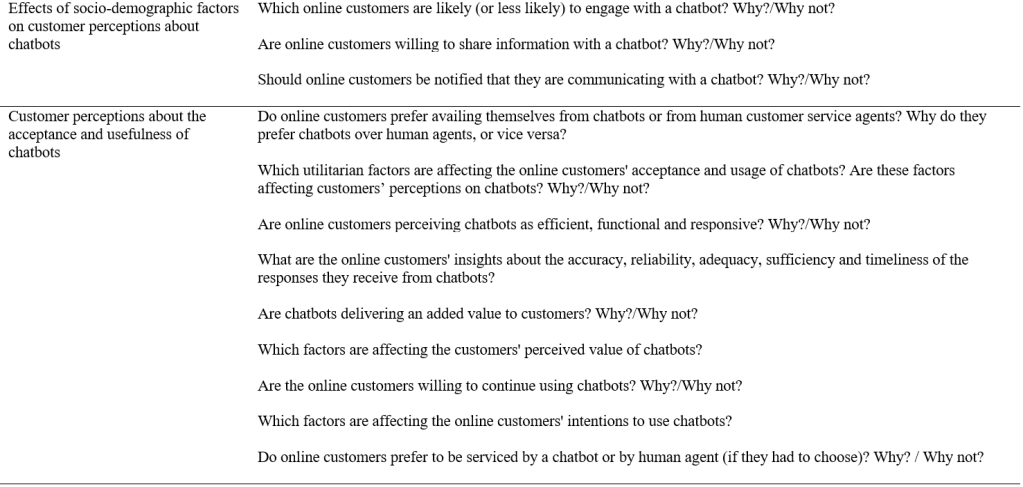

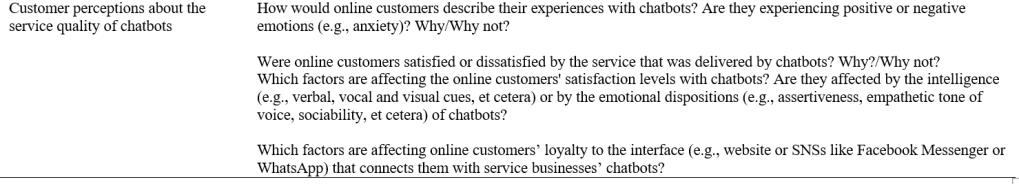

Ethical challenges are also conspicuous in customer service and frontline interactions (Han et al., 2023), where chatbots and virtual assistants handle large volumes of customer inquiries across retail, telecommunications and travel services (Lv et al., 2022). Although these systems offer efficiency and scalability benefits, there are instances where they fail to recognise emotional distress, cultural differences, or exceptional circumstances. Excessive automation can therefore undermine relational service quality, especially when customers are unable to escalate complex or sensitive issues to human agents (Yang et al., 2022).

In public service contexts, governments are progressively deploying AI systems (Willems et al., 2023) to allocate welfare benefits, determine assess eligibility and detect fraud. In such settings, automated decisions can have profound implications for the citizens’ livelihoods and their inclusion in cohesive societies Ethical concerns become particularly acute when accountability is diffused between public agencies and technology providers, as well as when affected individuals lack meaningful mechanisms for appeal, explanation or redress.

Likewise, platform-based and gig economy services are increasingly relying on algorithmic management systems to assign tasks, evaluate performance and to compute remunerations (Kadolkar et al., 2025). These systems often operate as “black boxes,” leaving workers uncertain about how ratings, penalties or income calculations are determined. The resulting lack of transparency and of clear accountability structures can weaken trust, exacerbate power asymmetries and could intensify worker vulnerability within ongoing service relationships.

Notwithstanding, more human resource management and recruitment specialists are adopting AI-enabled tools for résumé screening and to assess their candidates’ credentials (Soleimani et al., 2025). Possible bias embedded within these systems may disadvantage certain social groups. Their limited transparency can prevent applicants from understanding how hiring decisions are made. Such practices raise important ethical questions concerning fairness, informed consent and procedural justice within professional service contexts.

This special issue seeks to advance novel insights into the above ethical implications of AI and automation in services industries. The guest editors look forward to receiving original, interdisciplinary contributions that critically examine how ethical principles can be embedded into the design, governance, implementation and evaluation of AI-enabled service systems.

Aims and scope

The special issue aims to:

· Deepen understanding of ethical risks and dilemmas associated with AI and automation in service industries.

· Explore mechanisms for bias detection, mitigation and governance in service algorithms.

· Examine transparency, explainability and accountability in AI-enabled service encounters.

· Advance responsible, human-centered and sustainable approaches to AI-driven service innovation.

Both conceptual, theoretical and empirical contributions are welcome, including qualitative, quantitative, mixed-methods, experimental, design science as well as critical and/or reflexive approaches.

Indicative themes and topics

Submissions may address, but are not limited to, the following topics:

· Algorithmic bias and discrimination in service delivery;

· Ethical design of AI-enabled service systems;

· Transparency and explainability in automated service decisions;

· Accountability and responsibility in human–AI service interactions;

· AI ethics governance, regulation, and standards in service industries;

· Trust, legitimacy and customer perceptions of AI-driven services;

· Ethical implications of service robots and conversational agents;

· Human oversight and hybrid human–AI service models;

· Data privacy, surveillance and consent in digital service platforms;

· Fairness and inclusion in AI-based personalisation and targeting;

· Responsible AI and ESG considerations in service organisations;

· Cross-cultural and institutional perspectives on AI ethics in services;

· Ethical failures, service recovery and crisis communication involving AI;

· Methodological advances for studying ethics in AI-enabled services.

References

Camilleri, M. A., Zhong, L., Rosenbaum, M. S. & Wirtz, J. (2024). Ethical considerations of service organizations in the information age. The Service Industries Journal, 44(9-10), 634-660.

Camilleri, M. A. (2024). Artificial intelligence governance: Ethical considerations and implications for social responsibility. Expert Systems, 41(7), e13406.

Hu, Y., & Min, H. K. (2023). The dark side of artificial intelligence in service: The “watching-eye” effect and privacy concerns. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 110, 103437.

Kadolkar, I., Kepes, S., & Subramony, M. (2025). Algorithmic management in the gig economy: A systematic review and research integration. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 46(7), 1057-1080.

Kordzadeh, N., & Ghasemaghaei, M. (2022). Algorithmic bias: review, synthesis, and future research directions. European Journal of Information Systems, 31(3), 388-409.

Lv, X., Yang, Y., Qin, D., Cao, X., & Xu, H. (2022). Artificial intelligence service recovery: The role of empathic response in hospitality customers’ continuous usage intention. Computers in Human Behavior, 126, 106993.

Novelli, C., Taddeo, M., & Floridi, L. (2024). Accountability in artificial intelligence: What it is and how it works. AI & Society, 39(4), 1871-1882.

Procter, R., Tolmie, P., & Rouncefield, M. (2023). Holding AI to account: challenges for the delivery of trustworthy AI in healthcare. ACM Transactions on Computer-Human Interaction, 30(2), 1-34.

Soleimani, M., Intezari, A., Arrowsmith, J., Pauleen, D. J., & Taskin, N. (2025). Reducing AI bias in recruitment and selection: an integrative grounded approach. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 1-36.

Willems, J., Schmid, M. J., Vanderelst, D., Vogel, D., & Ebinger, F. (2023). AI-driven public services and the privacy paradox: do citizens really care about their privacy?. Public Management Review, 25(11), 2116-2134.

Yang, Y., Liu, Y., Lv, X., Ai, J., & Li, Y. (2022). Anthropomorphism and customers’ willingness to use artificial intelligence service agents. Journal of Hospitality Marketing & Management, 31(1), 1-23.

Submission Instructions

Submission guidelines

Manuscripts should be prepared according to The Service Industries Journal’s author guidelines and submitted via the journal’s online submission system. During submission, authors should select the special issue title:

“Ethical implications of artificial intelligence (AI) and automation in service industries: Addressing algorithmic bias, opacity and unclear accountability mechanisms”.

All submissions will undergo a double-blind peer review process in accordance with the journal’s standards and policies of Taylor & Francis.

Important dates

- Full paper submission deadline: 31st January 2027

- First round of reviews: 31st March 2027

- Revised manuscript submission: 31st May 2027

- Final acceptance: 31st August 2027

- Expected publication: 30th November 2027

Contact Information: For informal enquiries regarding the fit of manuscripts or the scope of the special issue, please contact the Leading Guest Editor via Mark.A.Camilleri@um.edu.mt.

You must be logged in to post a comment.