This is a pre-publication version of an academic paper, entitled; “Measuring the corporate managers’ attitudes toward ISO’s social responsibility standard”, that was accepted by Total Quality Management and Business Excellence (Print ISSN: 1478-3363 Online ISSN: 1478-3371).

How to Cite: Camilleri, M.A. (2018). Measuring the corporate managers’ attitudes toward ISO’s social responsibility standard. Total Quality Management & Business Excellence. (forthcoming). http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/14783363.2017.1413344

Abstract

The International Standards Organisation’s ISO 26000 on social responsibility supports organisations of all types and sizes in their responsibilities towards society and the environment. ISO 26000 recommends that organisations ought to follow its principles on accountability, transparency, ethical behaviours and fair operating practices that safeguard organisations and their stakeholders’ interests. Hence, this contribution presents a critical review of ISO 26000’s guiding principles. Afterwards, it appraises the business practitioners’ attitudes towards social responsibility practices, including organisational governance, human rights, labour practices, the environment, fair operating practices, consumer issues as well as community involvement and development. A principal component analysis has indicated that the executives were primarily committed to resolving grievances and on countering corruption. The results suggested that the respondents believed in social dialogue as they were willing to forge relationships with different stakeholders. Moreover, they were also concerned about environmental responsibility, particularly on mitigating climate change and sustainable consumption. In conclusion, this paper identifies the standard’s inherent limitations as it opens up future research avenues to academia.

Keywords: ISO 26000; International Standards Organisation; Social Responsibility; Organisational Governance; Human Rights; Labour Practices; environmental responsibility; fair operating practices; consumer issues; community involvement.

Introduction

The International Standard Organisation’s ISO 26000 provides guidance on social responsibility issues for businesses and other entities. This standard comprises broad issues, comprising labour practices, conditions of employment, responsible supply chain management, responsible procurement of materials and resources, fair operating practices, recommendations for negotiations with interested parties as well as collaborative stakeholder engagement among other issues (Helms, Oliver, & Webb, 2012; Castka & Balzarova, 2008a, 2008b, 2008c). ISO 26000 is aimed at all organisations, regardless of their activity, size or location. Its core subjects respect the international norms and assist organisations on accountability, transparency and ethical behaviours.

The social responsibility standard has emerged following lengthy partnerships’ agreements and negotiations between nongovernmental organisations (NGOs) and large multinational corporations (Helms et al., 2012; Boström & Halström, 2010; Castka & Balzarova, 2008a, 2008b, 2008c). Prior to ISO 26000, there were other certifiable and uncertifiable, multistakeholder standards and instruments; the Forest Stewardship Council (FSC), Greenpeace, Rainforest Alliance and Home Depot, among others (Balzarova & Castka, 2012; Castka & Corbett, 2016a). At the time, many organisations adopted voluntary environmental and social standards, as well as eco-labels such as ISO’s 14000, FSC, Fair Trade or the US Department of Agriculture’s USDA Organic Labelling. Like ISO 26000, their regulatory guidelines and principles encourage organisations and their stakeholders to become more socially responsible and environmentally sustainable. However, despite there are many standards and regulatory instruments, private businesses do not always provide credible information on their eco-labelling (Darnall, Ji, & Vazquez-Brust, 2016).

For this reason, environmental NGOs are putting pressure on national governments for more stringent compliance regulations on large undertakings to adhere to certified standards or ecolabels (Schwartz & Tilling, 2009). This approach could possibly inhibit the businesses and other organisations to reveal relevant information about their social responsibility and stakeholder engagement (Castka & Corbett, 2016b). Notwithstanding, there is still limited research and scant empirical evidence on how businesses are resorting to ISO 26000’s principles in their responsible managerial practices (see Hahn, 2013; Hahn & Weidtmann, 2016; Claasen & Roloff, 2012; Castka & Balzarova, 2008a, 2008b)Therefore, this contribution provides a review of the socially responsible standard’s guiding principles and appraises the executives’ attitudes towards ISO 26000. Firstly, it examines relevant theoretical insights and empirical studies on the managerial perceptions towards responsible organisational behaviours. Secondly, it sheds light on the development of ISO’s standard on social responsibility and its constituent elements. Thirdly, this paper reveals the managers’ perceptions of ISO 26000’s core topics, including organisational governance, human rights, labour practices, the environment, fair operating practices, consumer issues as well as community involvement and development. This research uses a principal component analysis (PCA) to obtain a factor solution of a smaller set of salient variables from ISO 26000’s core issues. The findings identify specific socially responsible activities which are being emphasised by the companies’ executives. The results suggest that the respondents were committed to improving their relationships with employees, marketplace as well as political and community stakeholders.

Literature review

The managerial perceptions of social responsibility

Several empirical studies have explored the managers’ attitudes towards and perceptions of corporate social responsibilities (Carollo & Guerci, 2017; Eweje & Sakaki, 2015; Moyeen & West, 2014; Fassin, Van Rossem, & Buelens, 2011; Pedersen, 2010; Basu & Palazzo, 2008; Nielsen & Thomsen, 2009 and Perrini, Russo, & Tencati, 2007, among others). A number of similar studies have gauged corporate social responsibility by adopting Fortune’s reputation index (Fryxell & Wang, 1994; Griffin & Mahon, 1997; Stanwick & Stanwick, 1998), the KLD index (Fombrun, 1998; Griffin & Mahon, 1997) or Van Riel and Fombrun’s (2007) RepTrak. Such measures required executives to assess the extent to which their company behaves responsibly towards the environment and the community (Fryxell & Wang, 1994). Despite their wide usage in past research, the appropriateness of these indices is still doubtful. For instance, Fortune’s reputation index failed to account for the multidimensionality of the corporate citizenship construct, and is suspected to be more significant of management quality than of corporate social performance (Waddock & Graves, 1997). Fortune’s past index suffered from the fact that its items were not based on theoretical arguments, as they did not appropriately represent the economic, legal, ethical and discretionary dimensions of the corporate citizenship construct.

Other academics, including Pedersen (2010), identified a set of common issues that were frequently used by managers when describing societal responsibilities. This study reported that managers still had a relatively narrow perception of societal responsibilities. Generally, they believed that CSR involves taking care of the workforce, and to manufacture products and deliver services that the customers want, in an eco-friendly manner. The managers who participated in Pedersen’s (2010) study did not believe that they had responsibilities towards society on issues such as social exclusion, Third World development and poverty reduction, among other variables. In a similar vein, Eweje and Sakaki (2015) pointed out that corporate social responsibility involved volunteering, diversity in the workplace and work–life balance. They contended that these are important areas that merit more attention, particularly for those businesses that are willing to prove their credentials. Moreover, Moyeen and West (2014) noticed that sustainable development and environmental issues often remained on the periphery of the managers’ understandings and perceptions of CSR

ISO’s social responsibility standard

In 2010, the development of ISO 26000 has represented a significant milestone in integrating socially and environmentally responsible behaviours into management processes (Toppinen, Virtanen, Mayer, & Tuppura, 2015; Hahn, 2013). ISO 26000 was developed through a participatory multi-stakeholder process with an emphasis on participatory decision-making and

democracy (Hahn & Weidtmann, 2016). For instance, the International Labour Organization (ILO) had established a Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) to ensure that ISO’s social responsibility standard is consistent with its very own labour standards. In fact, ISO 26000’s core subject on ‘Labour Practices’ is based on ILOs’ conventions on labour practices, including

Human Resources Development Convention, Occupational Health and Safety Guidelines, Forced Labour Convention, Freedom of Association, Minimum Wage Fixing Recommendation and the Worst Forms of Child Labour Recommendation, among others. Moreover, ISO’s core subject on ‘human rights’ is based on the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (adopted by the UN General Assembly in 1948).

The standard comprises seven essential areas in the realms of social responsibility: organisational governance, human rights, labour practices, environment, fair operating practices, consumer issues, and community involvement and development (ISO, 2014). ISO’s goal is to encourage organisations to integrate their guiding principles on social responsibility into their management strategies, systems and processes. Therefore, ISO 26000 assists in improving environmental, social and governance communications and also provides guidance on stakeholder identification and engagement (Camilleri, 2015a). It advises the practising organisations to take into account their varied stakeholders’ interests. According to Castka and Balzarova (2008a, p. 276), ‘ISO 26000 aims to assist organisations and their networks in addressing their social responsibilities as it provides practical guidance on how to operationalise CSR, by identifying and engaging with stakeholders and enhancing credibility of reports and claims made about CSR (Hąbek & Wolniak, 2016). Therefore, this standard has the potential to capture the context-specific nature of social responsibility.

ISO 26000 has been characterised as an evolutionary step in standard innovation because it is suitable for organisations of all sizes and sectors. This standard has unique features regarding authority and legitimacy (Hahn, 2013). Its guidelines describe social responsibility as ‘the actions a firm takes to contribute to “sustainable development”’ (Perez-Baltres, Doh, Miller, & Pisani, 2012, p. 158). Hahn (2013) suggested that ISO 26000 offers specific guidance on many facets of CSR, as it helps responsible businesses in their internal and external assessments and evaluations. Furthermore, when the organisations adopt ISO 26000, they could signal their social responsibility credentials and qualities to their marketplace stakeholders (Graffin & Ward, 2010). This way they may also reduce information asymmetries among supply chain partners (King, Lenox, & Terlaak, 2005).

ISO 26000 provides a unilateral understanding of social responsibility across the globe. It acknowledges that ‘social responsibility should be an integral part of the businesses’ core strategy (ISO, 2014). A wide array of social responsibility practices and stakeholder management issues are addressed in ISO 26000. This standard aims to unify and standardise social responsibility; it also acknowledges that each organisation has a responsibility to bear that are relevant to its business (Hąbek & Wolniak, 2016; Hahn, 2013). Notwithstanding, there are different industries, organisational settings, regional or cultural circumstances that will surely affect how entities implement the ISO standards ‘recommendations on responsible behaviours’.

The corporate culture is an important driver for socially responsible activities. Therefore, CEOs play a key role in giving their face and voice to their corporate sustainability agenda (Waldman et al., 2006; Caprar & Neville, 2012). Hence, ISO 26000 can be used as a vehicle for CSR communication. Hąbek and Wolniak (2016) suggested that this standard is rooted in a quality management framework, as it holds potential to enhance the credibility of the corporations’ social responsibility claims. Similarly, Moratis (2015) argued that the concept of credibility relates to scepticism, trust and greenwashing. Other research has demonstrated that some stakeholders have used standards to enhance their credibility, learning and legitimacy (Hąbek & Wolniak, 2016; Boström & Halström, 2010). Consequently, the organisations that are renowned for their genuine CSR credentials could garner a better reputation and image among stakeholders. This will ultimately result in significant improvements to the firms’ bottom lines. An organisational culture that promotes the sustainability agenda has the potential to achieve a competitive advantage, as businesses could improve their long-term corporate financial performance (Eccles, Ioannou, & Serafeim, 2012) via the development of valuable, rare and non-imitable organisational resources and capabilities (Barney, 1986). Eccles et al. (2012) analysed the financial performance of firms with either high or low sustainability orientation. The authors found that firms with a high sustainability orientation were associated with distinct governance mechanisms for sustainability, longer time horizons and deeper stakeholder engagement, as they dedicated more attention to non-financial disclosures. Their adoption of the sustainability standards, such as ISO 26000, can also be interpreted as a signal of a responsible corporate culture (Waldman et al., 2006).

On the other hand, many academic commentators argue that ISO 26000 has never been considered as a management standard. The certification requirements have not been incorporated into ISO 26000’s development and reinforcement process, unlike other standards, including ISO 9000 and ISO 14001(Hahn, 2013). In its present form, ISO 26000 does not follow a classical plan–do–check–act–type management system approach as it is the case for ISO 14001 (Hahn, 2013). Arimura, Darnall, and Katayama (2011) reported that the facilities that were certified with ISO’s 14000 were 40% more likely to assess their suppliers’ environmental performance and 50% more likely to require that their suppliers undertake specific environmental practices. Nevertheless, Arimura, Darnall, Ganguli, and Katayama (2016) argued that although ISO 14001 was a certifiable standard, the facilities that were adopting it were no more likely to reduce their air pollution emissions than noncertified ones.

Rasche and Kell (2010) admitted that the responsibility standards can never be a complete solution to the perennial social and environmental problems; they argued that the standards have inherent limitations that need to be recognised. Certain prestandardisation preparations may have created boundaries which have restricted the stakeholders’ influence. Suchman (1995) described the pre-standardisation phase as an effort which embedded new structures and practices into already legitimate institutions. During the pre-standardisation discussions among stakeholders, there were differing opinions and not enough consensus over ISO 26000’s certification (Mueckenberger & Jastram, 2010). Other authors declared that the certification of standards does not necessarily lead to improved performance (Aravind & Christmann, 2011; King et al., 2005). The development of ISO 26000 involved lengthy, multi-stakeholder corroborations that did not necessarily ensure legitimacy or guarantee that the standard could be considered as an enforceable instrument for industry participants. Balzarova and Castka (2012) also pointed out that the scope of the ISO 26000 standard was unclear as the actual implications for social and environmental improvement were still unknown. Many stakeholders, including chief executives, should have been in a position to leverage their arguments during the pre-standardisation arrangements (Balzarova & Castka, 2012). The responsible businesses could have discussed possible avenues for the standard’s reinforcement. For instance, those organisations that are in complete compliance with ISO 26000 are not required to disclose their social responsibility reports and to make them readily accessible to stakeholders (Balzarova & Castka, 2012). This contentious issue could lead organisations to not fully conform themselves to this uncertifiable standard.

Different industry representatives were (and are still) concerned that costly certification requirements could overburden organisations, particularly in emerging economies. The organisations’ stakeholders, including their employees, may be against the introduction of new standards as they could affect their firms’ bottom lines. When the standards are enforced, industry stakeholders need to comply with their requirements. The companies will usually have to absorb the cost of compliance with the standards (Delmas, 2002). Moreover, the standards may also lead to the creation of trade barriers and to significant increases in production costs (Montabon, Melnyk, Sroufe, & Calantone, 2000). Notwithstanding, when introducing new standards, the standard setters’ external audits could reveal regulatory non-compliance among adopting organisations (Schwartz & Tilling, 2009; Delmas, 2002). As a result, the industries’ implementation of a new standard such as ISO 26000 could be time-consuming because it may require holistic adaptations to change extant organisational processes. The standardisation of social responsibility has also been criticised for being costly and thereby difficult to implement, especially among the smaller companies (Toppinen et al., 2015).

Ávila et al.’s (2013) survey indicated that ISO 26000’s themes were under-represented, particularly those involving labour practices and the environment. The authors posited that the organisations that were supposedly following ISO 26000 have often faced difficulties in incorporating the social responsibility throughout all organisational mechanisms, processes and decisions. Ávila et al. (2013) argued that the businesses’ unsatisfactory engagement with consumer issues was even more serious, as they justify the organisations’ existence. It may appear that Ávila et al.’s (2013) research participants were only concerned about their corporate image (as they were supposedly implementing the social responsibility concept and its premises). Evidently, these firms were less interested in undertaking necessary actions to ensure truthful and fair compliance with ISO 26000.

Methodology

This research has explored the senior executives’ stance on ISO’s social responsibility standard. The respondents were all employed by listed companies in a small European member country. They were expected to indicate their attitudes towards and perceptions of ISO 26000’s core topics, including organisational governance, human rights, labour practices, the environment, fair operating practices, consumer issues as well as community involvement and development. The questionnaire’s design, layout and content were consistent with the social responsibility standard. Respondents were asked to indicate the strength of their agreement or disagreement with ISO 26000’s subjects. The survey instrument made use of the five-point Likert scaling mechanism, where a numerical value was attributed to the informant’s opinion and perception. The responses were coded from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree) with 3 signalling indecision. Such symmetric, equidistant scaling has provided an interval level of measurement.

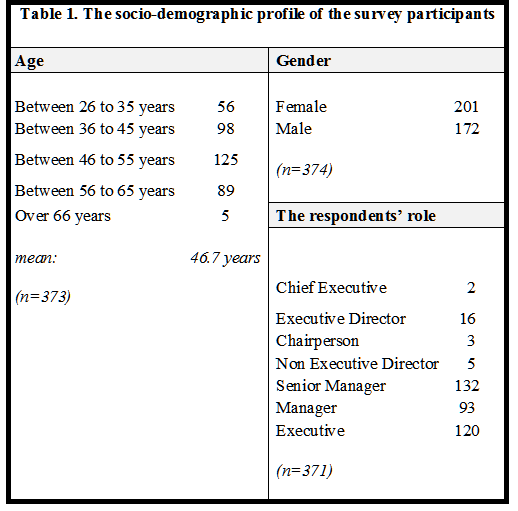

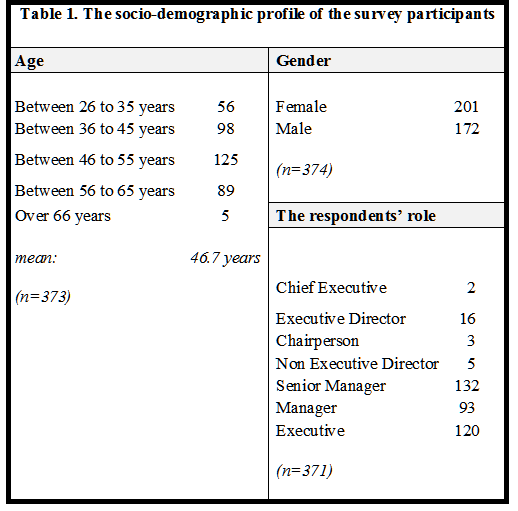

An online questionnaire link was sent electronically by means of an email, directly to the senior executives of all companies that were listed on the Malta Stock Exchange. There were numerous attempts to ensure that the questionnaire has been received by all email recipients. Many steps were taken to ensure a high response rate, which included reminder emails and numerous telephone calls. Eventually, there was a total of 374 (out of 1626) respondents who have willingly chosen to take part in this research. This sample represented a usable response rate of 23% of all targeted research participants. The surveyed respondents gave their socio-demographic details about their ‘role’, ‘age’, ‘gender’ and ‘education’ in the latter part of the survey questionnaire. The objective of this designated profile of owner-managers was to gain a good insight into their ability to make evaluative judgements in taking strategic decisions on social responsibility matters. Table 1 presents the profile of respondents who participated in this study.

Following the data gathering process, the researcher carried out descriptive statistics to analyse the distribution and dispersion of the data. Afterwards, factor analysis (FA) data reduction techniques were used to achieve the desired reliability, timely and accurate assessment of the findings. Unless an instrument is reliable, it cannot be valid. The FA was developed to explore and discover the main construct or dimension in the data matrix. The primary objective of this analysis was to reduce the number of variables in the data-set and to detect any underlying structure between them (Hair, Anderson, Tatham, & Black, 1998). Therefore, FA identified the interrelationships among variables. FA extracted components to obtain a factor solution of a smaller set of salient variables which exhibited the highest variation from the linear combination of original variables (Hair et al., 1998). It then removed this variance and produced a second linear combination which explained the maximum proportion of the remaining variance. The first step was to decide which factor components were going to be retained in the PCA. This approach was considered appropriate as there were variables that shared close similarities and highly significant correlations. The criterion for retaining factors is that each retained component must have some sort of face validity and/or theoretical validity, but prior to the rotation process, it was impossible to interpret what each factor meant. The first component accounted for a fairly large amount of the total variance. Each succeeding component had smaller amounts of variance. Although a large number of components could be extracted, only the first few components will be important enough to be retained for interpretation.

The SPSS default was set to keep any factor with an eigenvalue larger than 1.0. If a factor component displayed an eigenvalue less than 1.0, it would have explained less variance than the original variable. Once the factors have been chosen, the next step was to rotate them. The goal of rotation was to achieve what is called a ‘simple structure’, with high factor loadings on one factor and low loadings on all others. The factor loading refers to the correlation between each retained factor and each of the original variables. With regard to determining the significance of the factor loading, this study had followed the guidelines for identifying significant factor loadings based on the specific sample size, as suggested by Hair et al. (1998).

Analysis

The survey questionnaires’ responses were imported directly into SPSS. After filtering responses and eliminating unusable or incomplete survey observations, a total of 374 valid responses were obtained. The managers of the listed companies were required to indicate their level of agreement with ISO 26000 core subjects. Reliability and appropriate validity tests have been carried out during the analytical process. Cronbach’s alpha was calculated to test for the level of consistency among the items.

Principal component analysis

Bartlett’s test of sphericity revealed sufficient correlation in the data-set to run a PCA since P< .001. The Kaiser–Meyer– Olkin’s Test (which measures the sampling adequacy) was also acceptable, as it was well above 0.5. With respect to scale reliability, all constructs were analysed for internal consistency by using Cronbach’s alpha. The composite reliability coefficient (Bagozzi & Yi, 1988) was 0.79, well above the minimum acceptance value of 0.7.

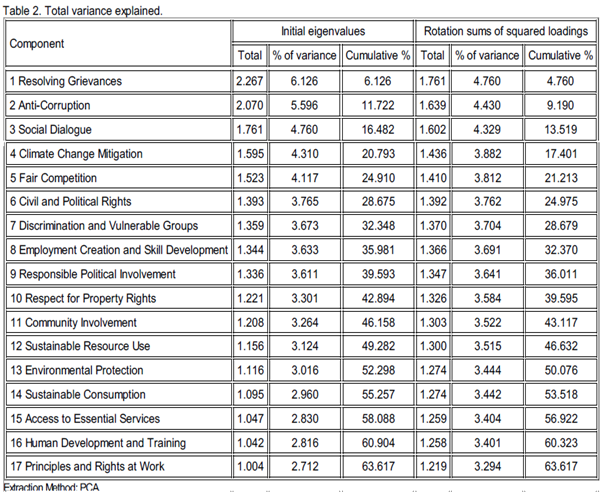

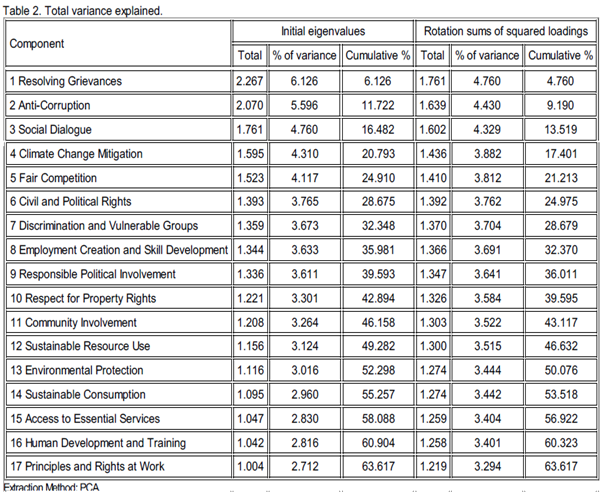

PCA has been chosen to obtain a factor solution of a smaller set of salient variables, from a much larger data-set. A varimax rotation method was used to spread variability more evenly among the constructs. PCA was considered appropriate as there were variables exhibiting an underlying structure. Many variables shared close similarities as there were highly significant correlations. Therefore, PCA has identified the patterns within the data and expressed it by highlighting the relevant similarities (and differences) in each and every component. In the process, the data have been compressed as it was reduced in a number of dimensions without much loss of information. From SPSS, the PCA has produced a table which illustrated the amount of variance in the original variables (with their respective initial eigenvalues), which were accounted for every component. There was also a percentage of variance column which indicated the expressed ratio, as a percentage of the variance (for each component). A brief description of the extracted factor components, together with their eigenvalues and their respective percentage of variance, is provided in Table 2 . The sum of the eigenvalues equalled the number of components. Only principal components with eigenvalues greater than 1 were extracted, and they accounted for more than 63% variance before rotation. The PCA analysis yielded 17 extracted components from ISO 26000’s 37 variables. These factor components were labelled following a cross-examination of the variables with the higher loadings. Typically, the variables with the highest correlation scores had mostly contributed towards the make-up of the respective component.

Discussion and conclusions

Many stakeholders, particularly the regulatory ones, from the most advanced economies are increasingly inquiring about the corporations’ responsible behaviours. Very often, multinational businesses are resorting to the NGOs’ tools and instruments, such as process and performance-oriented standards in corporate governance, human rights, labour, environmental

protection, anti-corruption as well as health and safety, among others (Camilleri, 2015a). In this light, ISO 26000 standard has been chosen to investigate company executives’ stance towards social responsibility practices.

This empirical research suggests that the respondents’ responsible and sustainable behaviours were both internally and externally focused. The managers indicated that they were paying attention to their human rights issues, labour and fair operating practices. Table 2 reported that the executives gave due importance to resolving grievances and anti-corruption within their organisation. This finding is consistent with other contributions which link CSR with the human resources management literature (Currie, Gormley, Roche, & Teague, 2016; Hahn, 2013; Wettstein, 2012; Pedersen, 2010; Ewing, 1989). The workplace conflict may be intrinsic to the nature of work, because employees and managers may have hard-to-reconcile competing interests (Currie et al., 2016). Ewing (1989) argued that companies develop grievance procedures to help them in their due processes. The author maintained that its development leads to better morale and productivity, fewer union interventions and less likelihood of being sued. However, grievance procedures could incur operating costs, often consume large amounts of previous time from executives and may open the door to chronic malcontents.

This study evidenced that the corporations’ managers were clearly against corrupt practices. Today’s listed businesses are increasingly expected to explain how they are fighting fraudulent activities and bribery issues. This study was conducted in a European Union jurisdiction which mandates a ‘comply or explain’ directive on non-financial reporting (Camilleri, 2015b). The European corporations are expected to be as transparent as possible, to disclose material information and to limit the pursuit of exploitative, unfair or deceptive practices (Camilleri, 2015b). Moreover, large organisations that are operating in member states (that have ratified the ILO’s conventions on labour rights) are morally and legally bound to promote fair operating practices and to engage in social dialogue. The findings suggest that the respondents were committed to forging relationships with different stakeholders, including suppliers and market intermediaries, the wider communities at large, as well as political groups, among others. Porter and Kramer (2011) contended that capable local suppliers foster greater logistical efficiency and ease of collaboration in areas, such as training, in order to boost productivity. Therefore, the success of every company is affected by supporting stakeholders and the extant infrastructure around it. The big businesses’ stakeholder engagement is rooted in institutional theory, as they are capable of aligning themselves with their broader context (Brammer, Jackson, & Matten, 2012). In fact, this study has also measured the respondents’ attitudes on social engagement (including the creation of jobs and skills development, the conditions of employment and the individuals’ civil and political rights) and on the subject of discrimination towards vulnerable groups, among other contingent topics. Moreover, the listed companies’ executives also indicated that they were concerned on environmental sustainability, particularly on global climate change. The corporations’ managers did not explain how they were committed to reduce the carbon footprint or prevent the emission of greenhouse gases. However, they may use new technologies, including renewable energy, water use and conservation. Alternatively, they could change older equipment to reduce pollution and make it more efficient and economical. The results suggest that respondents respected property rights, they utilised and consumed sustainable resources, and were concerned on protecting the natural environment.

Limitations and suggestions for future research

The extant literature has recognised this ISO 26000’s inherent limitations. For the time being, the businesses that are using this standard are not required to disclose material information on their social responsibility practices to stakeholders. One of the most contentious issues is that ISO 26000 still remains voluntary and uncertifiable. The practitioners may ultimately decide not to fully conform themselves with this standard, as they are not bound to do so. For this reason, ISO 26000’s role is still limited for regulators, standard-setting organisations and policy-makers.

In a nutshell, this paper has advanced an empirical study that explored the business executives’ appraisal of social responsibility practices. It has employed ISO 26000 as a comprehensive measure for organisational governance, human rights, labour practices, the environment, fair operating practices, consumer issues, and community involvement and development. Moreover, this contribution has critically analysed key theoretical underpinnings and previous empirical studies on the social responsibility standard. Further research may yield other conclusions about how responsible organisations and corporations could use this standard to appraise their social responsibility endeavours. Future studies could explore different stakeholders’ views, other than the corporation executives’ stance on ISO 26000 subjects. Academia could utilise ISO’s broad standard as a measure for social responsibility behaviours. Moreover, qualitative research could clarify in depth and breadth how organisations are mapping their progress and advancement in the implementation and monitoring of the standard’s responsible initiatives. Future research could identify certain difficulties in incorporating the social responsibility standard throughout the organisational systems and processes.

Acknowledgements

The author thanks this journal’s editor and his anonymous reviewers for their insightful remarks and suggestions.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

References

Aravind , D., & Christmann , P. (2011). Decoupling of standard implementation from certification: Does quality of ISO 14001 implementation affect facilities’ environmental performance? Business Ethics Quarterly, 21(01), 73–102. doi:10.5840/beq20112114

Arimura , T. H., Darnall , N., Ganguli , R., & Katayama , H. (2016). The effect of ISO 14001 on environmental performance: Resolving equivocal findings. Journal of Environmental Management, 166, 556–566. doi:10.1016/j.jenvman.2015.10.032

Arimura , T. H., Darnall , N., & Katayama , H. (2011). Is ISO 14001 a gateway to more advanced voluntary action? The case of green supply chain management. Journal of Environmental Economics and Management, 61, 170–182. doi:10.1016/j.jeem.2010.11.003

Ávila , L. V., Hoffmann , C., Corrêa , A. C., Rosa Gama Madruga , L. R., Schuch Júnior , V. F., Júnior , S., … Zanini , R. R. (2013). Social responsibility initiatives using ISO 26000: An analysis from Brazil. Environmental Quality Management, 23(2), 15–30. doi:10.1002/tqem.21362

Bagozzi , R. P., & Yi , Y. (1988). On the evaluation of structural equation models. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 16(1), 74–94. doi:10.1007/BF02723327

Balzarova , M. A., & Castka , P. (2012). Stakeholders’ influence and contribution to social standards development: The case of multiple stakeholder approach to ISO 26000 development. Journal of Business Ethics, 111(2), 265–279. doi:10.1007/s10551-012-1206-9

Barney , J. B. (1986). Organisational culture: Can it be a source of sustained competitive advantage? Academy of Management Review, 11(3), 656–665. doi:10.2307/258317

Basu , K., & Palazzo , G. (2008). Corporate social responsibility: A process model of sensemaking. Academy of Management Review, 33(1), 122–136. doi:10.5465/AMR.2008.27745504

Boström M., & Hallström K.T.. (2010). NGO power in global social and environmental standard-setting. Global Environmental Politics, 10(4), 36–59.

Brammer , S., Jackson , G., & Matten , D. (2012). Corporate social responsibility and institutional theory: New perspectives on private governance. Socio-Economic Review, 10(1), 3–28. doi:10.1093/ser/mwr030

Camilleri , M. A. (2015a). Valuing stakeholder engagement and sustainability reporting. Corporate Reputation Review, 18(3), 210–222. doi:10.1057/crr.2015.9

Camilleri , M. A. (2015b). Environmental, social and governance disclosures in Europe. Sustainability Accounting, Management and Policy Journal, 6(2), 224–242. doi:10.1108/SAMPJ-10-2014-0065

Caprar , D. V., & Neville , B. A. (2012). “Norming” and “conforming”: Integrating cultural and institutional explanations for sustainability adoption in business. Journal of Business Ethics, 110(2), 231–245. doi:10.1007/s10551-012-1424-1

Carollo , L., & Guerci , M. (2017). Between continuity and change: CSR managers’ occupational rhetorics. Journal of Organizational Change Management, 30(4), 632–646. doi:10.1108/JOCM-05-2016-0073

Castka , P., & Balzarova , M. A. (2008a). ISO 26000 and supply chains – On the diffusion of the social responsibility standard. International Journal of Production Economics, 111(2), 274–286. doi:10.1016/j.ijpe.2006.10.017

Castka , P., & Balzarova , M. A. (2008b). The impact of ISO 9000 and ISO 14000 on standardisation of social responsibility – An inside perspective. International Journal of Production Economics, 113(1), 74–87. doi:10.1016/j.ijpe.2007.02.048

Castka , P., & Balzarova , M. A. (2008c). Social responsibility standardization: Guidance or reinforcement through certification? Human Systems Management, 27, 231–242.

Castka , P., & Corbett , C. J. (2016a). Governance of eco-labels: Expert opinion and media coverage. Journal of Business Ethics, 135(2), 309–326. doi:10.1007/s10551-014-2474-3

Castka , P., & Corbett , C. J. (2016b). Adoption and diffusion of environmental and social standards. International Journal of Operations and Production Management, 36, 1509–1524. doi:10.1108/IJOPM-01-2015-0037

Claasen C., & Roloff J.. (2012). The link between responsibility and legitimacy: The case of De Beers in Namibia. Journal of Business Ethics, 107(3), 379–398.

Currie , D., Gormley , T., Roche , B., & Teague , P. (2016). The management of workplace conflict: Contrasting pathways in the HRM literature. International Journal of Management Reviews. Retrieved from http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/ijmr.12107/full

Darnall , N., Ji , H., & Vazquez-Brust , D. A. (2016). Third-party certification, sponsorship and consumers’ ecolabel use. Journal of Business Ethics, doi:10.1007/s10551-016-3138-2

De Colle , S., Henriques , A., & Sarasvathy , S. (2014). The paradox of corporate social responsibility standards. Journal of Business Ethics, 125(2), 177–191. doi:10.1007/s10551-013-1912-y

Delmas , M. A. (2002). The diffusion of environmental management standards in Europe and the United States: An institutional perspective. Policy Sciences, 35, 91–119. doi:10.1023/A:1016108804453

Eccles , R. G., Ioannou , I., & Serafeim , G. (2012). The impact of a corporate culture of sustainability on corporate behaviour and performance (No. W17950). National Bureau of Economic Research. Harvard Business School Working Paper, Cambridge, MA, USA.

Eweje , G., & Sakaki , M. (2015). CSR in Japanese companies: Perspectives from managers. Business Strategy and the Environment, 24(7), 678–687. doi:10.1002/bse.1894

Ewing , D. W. (1989). Justice on the job: Resolving grievances in the nonunion workplace. Cambridge, MA: Harvard Business Press.

Fassin , Y., Van Rossem , A., & Buelens , M. (2011). Small-business owner-managers’ perceptions of business ethics and CSR-related concepts. Journal of Business Ethics, 98(3), 425–453. doi:10.1007/s10551-010-0586-y

Figge , F., Hahn , T., Schaltegger , S., & Wagner , M. (2002). The sustainability balanced scorecard–linking sustainability management to business strategy. Business Strategy and the Environment, 11(5), 269–284. doi:10.1002/bse.339

Fombrun , C. J. (1998). Indices of corporate reputation: An analysis of media rankings and social monitors’ ratings. Corporate Reputation Review, 1(4), 327–340. doi:10.1057/palgrave.crr.1540055

Fryxell , G. E., & Wang , J. (1994). The fortune corporate ‘reputation’ index: Reputation for what? Journal of Management, 20(1), 1–14. doi:10.1177/014920639402000101

Graffin , S. D., & Ward , A. J. (2010). Certifications and reputation: Determining the standard of desirability amidst uncertainty. Organisation Science, 21(2), 331–346. doi:10.1287/orsc.1080.0400

Griffin , J. J., & Mahon , J. F. (1997). The corporate social performance and corporate financial performance debate twenty five years of incomparable research. Business & Society, 36(1), 5–31. doi:10.1177/000765039703600102

Hahn , R. (2013). ISO 26000 and the standardization of strategic management processes for sustainability and corporate social responsibility. Business Strategy and the Environment. Retrieved from http://ssrn. com/abstract, 2094226

Hahn , R., & Weidtmann , C. (2016). Transnational governance, deliberative democracy, and the legitimacy of ISO 26000 analyzing the case of a global multistakeholder process. Business & Society, 55(1), 90–129. doi:10.1177/0007650312462666

Hair Jr., J. F., Anderson , R. E., Tatham , R. L., & Black , W. C. (1998). Multivariate data analysis (5th ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Hąbek , P., & Wolniak , R. (2016). Assessing the quality of corporate social responsibility reports: The case of reporting practices in selected European Union member states. Quality & Quantity, 50(1), 399–420. doi:10.1007/s11135-014-0155-z

Helms , W. S., Oliver , C., & Webb , K. (2012). Antecedents of settlement on a new institutional practice: Negotiations of the

ISO 26000 standard on social responsibility. Academy of Management Journal, 55, 1120–1145. doi:10.5465/amj.2010.1045

ISO. (2014). ISO 26000: Guidance on Social Responsibility. Retrieved from http://www.iso.org/iso/discovering_iso_26000.pdf

King , A. A., Lenox , L. J., & Terlaak , A. (2005). The strategic use of decentralized institutions: Exploring certification with the

ISO 14001 management standard. Academy of Management Journal, 48(6), 1091–1106. doi:10.5465/AMJ.2005.19573111

Montabon , F., Melnyk , S. A., Sroufe , R., & Calantone , R. J. (2000). ISO 14000: Assessing its perceived impact on

corporate performance. Journal of Supply Chain Management, 36(1), 4–16. doi:10.1111/j.1745-493X.2000.tb00073.x

Moratis , L. (2015). The credibility of corporate CSR claims: A taxonomy based on ISO 26000 and a research agenda. Total Quality Management & Business Excellence, 1–12.

Moyeen , A., & West , B. (2014). Promoting CSR to foster sustainable development: Attitudes and perceptions of managers in a developing country. Asia-Pacific Journal of Business Administration, 6(2), 97–115. doi:10.1108/APJBA-05-2013-0036

Mueckenberger , U., & Jastram , S. (2010). Transnational norm-building networks and the legitimacy of corporate social responsibility standards. Journal of Business Ethics, 97(2), 223–239. doi:10.1007/s10551-010-0506-1

Nielsen , A. E., & Thomsen , C. (2009). Investigating CSR communication in SMEs: A case study among Danish middle managers. Business Ethics: A European Review, 18(1), 83–93. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8608.2009.01550.x

Pedersen , E. R. (2010). Modelling CSR: How managers understand the responsibilities of business towards society. Journal of Business Ethics, 91(2), 155–166. doi:10.1007/s10551-009-0078-0

Perez-Baltres , L., Doh , J., Miller , V., & Pisani , M. (2012). Stakeholder pressures as determinants of CSR strategic choice: Why do firms choose symbolic versus substantive self-regulatory codes of conduct? Journal of Business Ethics, 110, 157–172.

Perrini , F., Russo , A., & Tencati , A. (2007). CSR strategies of SMEs and large firms. Evidence from Italy. Journal of Business Ethics, 74(3), 285–300. doi:10.1007/s10551-006-9235-x

Porter , M., & Kramer , M. (2011). The big idea: Creating shared value. Harvard Business Review, 89(1/2), 62–77.

Rasche , A., & Kell , G. (2010). The United Nations global compact: Achievements, trends and challenges. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

Schwartz , B., & Tilling , K. (2009). ‘ISO-lating’ corporate social responsibility in the organizational context: A dissenting interpretation of ISO 26000. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management, 16(5), 289–299. doi:10.1002/csr.211

Stanwick , P. A., & Stanwick , S. D. (1998). The relationship between corporate social performance, and organizational size, financial performance, and environmental performance: An empirical examination. Journal of Business Ethics, 17(2), 195–204.

Suchman , M. C. (1995). Managing legitimacy: Strategic and institutional approaches. Academy of Management Review, 20, 571–610.

Toppinen , A., Virtanen , A., Mayer , A., & Tuppura , A. (2015). Standardizing social responsibility via ISO 26000: Empirical insights from the forest industry. Sustainable Development, 23(3), 153–166. doi:10.1002/sd.1579

Van Riel , C. B., & Fombrun , C. J. (2007). Essentials of corporate communication: Implementing practices for effective reputation management. Abingdon: Routledge.

Waddock , S. A., & Graves , S. B. (1997). The corporate social performance-financial performance link. Strategic Management Journal, 18(4), 303–319. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1097-0266(199704)18:4<303::AID-SMJ869>3.0.CO;2-G

Waldman , D. A., de Luque , M. S., Washburn , N., House , R. J., Adetoun , B., Barrasa , A., … Wilderom , F. (2006). Cultural and leadership predictors of corporate social responsibility values of top management: A GLOBE study of 15 countries. Journal of International Business Studies, 37(6), 823–837. doi:10.1057/palgrave.jibs.8400230

Wettstein , F. (2012). CSR and the debate on business and human rights: Bridging the great divide. Business Ethics Quarterly, 22(4), 739–770. doi:10.5840/beq20122244

You must be logged in to post a comment.