Featuring a few snippets from one of my latest co-authored papers on the use of sustainable technologies in different industry sectors. A few sections have been adapted to be presented as a blog post.

Suggested citation: Varriale, V., Camilleri, M. A., Cammarano, A., Michelino, F., Müller, J., & Strazzullo, S.(2024). Unleashing digital transformation to achieve the sustainable development goals across multiple sectors. Sustainable Development, https://doi.org/10.1002/sd.3139

Abstract: Digital technologies have the potential to support the achievement of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). Existing scientific literature lacks a comprehensive analysis of the triple link: “digital technologies – different industry sectors – SDGs”. By systematically analyzing extant literature, 1098 sustainable business practices are identified from 578 papers. The researchers noted that 11 digital technologies are employed across 17 industries to achieve the 17 SDGs. They report that artificial intelligence can be used to achieve affordable and clean energy (SDG 7), responsible consumption and production (SDG 12) as well as to address climate change (SDG 13). Further, geospatial technologies may be applied in the agricultural industry to reduce hunger in various domains (SDG 2), to foster good health and well‐being (SDG 3), to improve the availability of clean water and sanitation facilities (SDG 6), raise awareness on responsible consumption and production (SDG 12), and to safeguard life on land (SDG 15), among other insights.

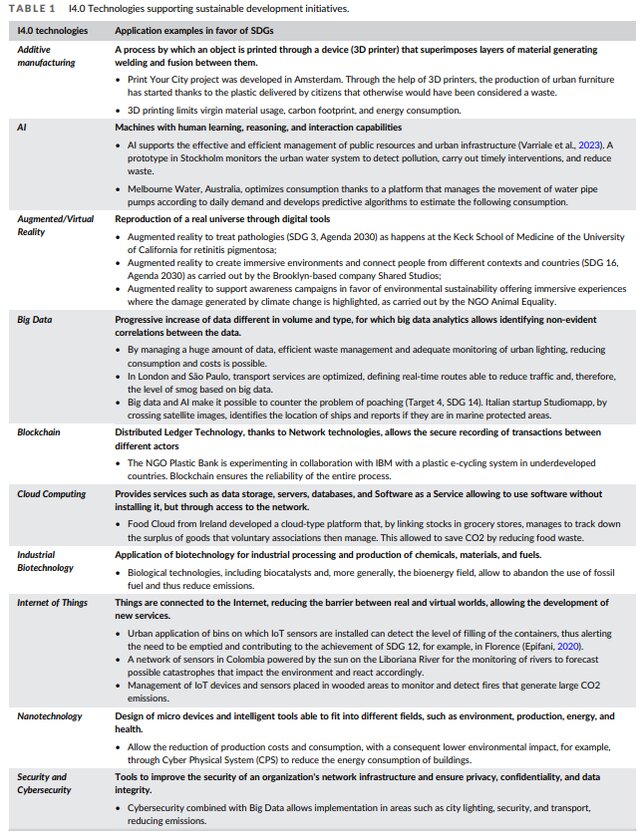

Literature review: The integration of digital technologies has emerged as a transforma-tive force in advancing sustainability objectives across diverse sectorsand industries. Digital technologies offer unprecedented opportunitiesto enhance resource efficiency, optimize processes, and foster innovation, thereby facilitating progress toward the attainment of the SDGs (Birkel & Müller, 2021; Camilleri et al., 2023; Cricelli et al., 2024). Table 1 sheds light on digital technologies that can be used to achieve the sustainable development goals.

Table 2 provides a list of digital technologies (Perano et al., 2023). These disruptive innovations were used as keywords in the search string through SCOPUS.

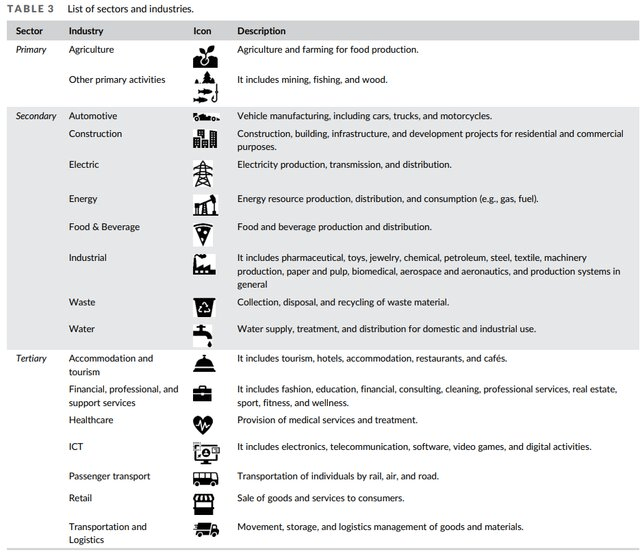

Table 3 identifies sectors and industries based on the SIC code classification (United Kingdom Government, 2024).

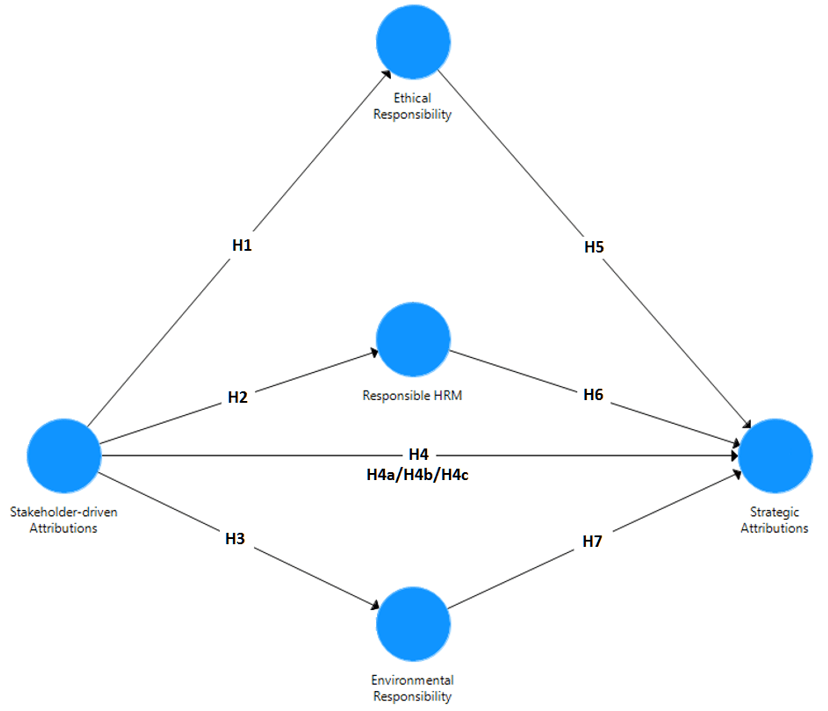

Theoretical implications: This article offers a comprehensive overview of the intersection between digitalization and sustainability across various industry sectors. It also considers their peculiar characteristics. The research analyzed 578 articles and identified 1098 sustainable business practices (SBPs), which were categorized into a three-dimensional framework connecting digital technologies, sectors & industries, as well as SDGs. This approach provides a new and innovative perspective on combining sustainability and digitalization by highlighting both promising and established areas of digital technology implementation. Theoretically, this study presents a clear and comprehensive picture of how digital technologies are adopted in different industries to achieve the SDGs. It classifies SBPs into three dimensions: (a) digital technology, (b) sectors & industries, and (c) SDGs. The goal is to present an up-to-date and thorough representation of digital technologies used to achieve the SDGs, based on information from scientific articles.

This contribution sheds light on key opportunities for the application of digital technologies. It identifies specific areas where they can be most effective. Unlike other research studies, this study uses a database of SBPs that can be applied across different industry sectors, to explain how practitioners can enhance their sustainability performance and achieve the SDGs. The three-dimensional framework illustrated in this article allows stakeholders to better understand how to adapt their business strategies and day-to-day operations to increase their sustainability credentials and to reduce their environmental impacts.

Managerial and policy implications: This research provides a comprehensive overview of the implementation of digital technologies across various industries and sectors. It raises awareness on how they can be utilized to achieve the SDGs. It highlights established applications of technologies and also identifies new ones. The proposed framework associates various digital technologies with specific industry sectors. It clearly explains who they can be employed to achieve the SDGs. Hence, this research and its findings would surely benefit practitioners, managers, and policy-makers.

The rationale behind this contribution is to build a robust knowledge base about the use of sustainable technologies among stakeholders. This way, they will be in a better position to improve their corporate responsibility credentials. Managers can use this study’s proposed framework to gain a deeper understanding of SBPs at three levels. In a nutshell, this research posits that SBPs can support practitioners in their strategic and operational decisions while minimizing the risks associated with adopting technologies that are less effective in addressing sustainability challenges. Additionally, this paper offers valuable insights for policymakers. It implies that research funds ought to be allocated toward specific sustainable technologies. This way, they can support various industry sectors in a targeted manner, and foster the development of digital transformation for the achievement of different SDGs.

The full paper (a prepublication version) is available from: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/382632705_Unleashing_digital_transformation_to_achieve_the_sustainable_development_goals_across_multiple_sectors

You must be logged in to post a comment.