Implications to academia

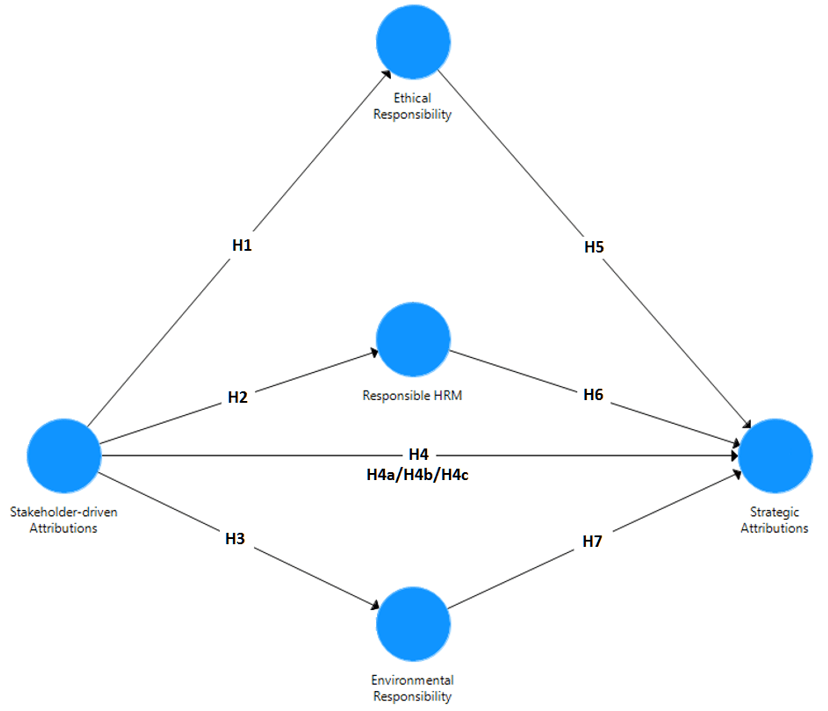

This research model suggests that the businesses’ socially and environmentally responsible behaviors are triggered by different stakeholders. The findings evidenced that stakeholder-driven attributions were encouraging tourism and hospitality companies to engage in responsible behaviors, particularly toward their employees. The results confirmed that stakeholders were expecting these businesses to implement environmentally friendly initiatives, like recycling practices, water and energy conservation, et cetera. The findings revealed that there was a significant relationship between stakeholder attributions and the businesses’ strategic attributions to undertake responsible and sustainable initiatives.

This contribution proves that there is scope for tourism and hospitality firms to forge relationships with various stakeholders. By doing so, they will add value to their businesses, to society and the environment. The respondents clearly indicated that CSR initiatives were having an effect on marketplace stakeholders, by retaining customers and attracting new ones, thereby increasing their companies’ bottom lines.

Previous research has yielded mixed findings on the relationships between corporate social performance and their financial performance (Inoue & Lee, 2011; Kang et al., 2010; Orlitzky, Schmidt, & Rynes, 2003; McWilliams and Siegel 2001). Many contributions reported that companies did well by doing good (Camilleri, 2020a; Falck & Heblich, 2007; Porter & Kramer, 2011). The businesses’ laudable activities can help them build a positive brand image and reputation (Rhou et al., 2016). Hence, there is scope for the businesses to communicate about their CSR behaviors to their stakeholders. Their financial performance relies on the stakeholders’ awareness of their social and environmental responsibility (Camilleri, 2019a).

Arguably, the traditional schools of thought relating to CSR, including the stakeholder theory or even the legitimacy theory had primarily focused on the businesses’ stewardship principles and on their ethical or social responsibilities toward stakeholders in society (Carroll, 1999; Evan & Freeman, 1993; Freeman, 1986). In this case, this study is congruent with more recent contributions that are promoting the business case for CSR and environmentally-sound behaviors (e.g. Dmytriyev et al., 2021; Carroll, 2021; Camilleri, 2012; Carroll & Shabana 2010; Falck & Heblich, 2007).

This latter perspective is synonymous with value-based approaches, including ‘The Virtuous Circles’ (Pava & Krausz 1996), ‘The Triple Bottom Line Approach’ (Elkington 1998), ‘The Supply and Demand Theory of the Firm’ (McWilliams & Siegel 2001), ‘the Win-Win Perspective for CSR practices’ (Falck & Heblich, 2007), ‘Creating Shared Value’ (Porter & Kramer 2011), ‘Value in Business’ (Lindgreen et al., 2012), ‘The Stakeholder Approach to Maximizing Business and Social Value’ (Bhattacharya et al., 2012), ‘Value Creation through Social Strategy’ (Husted et al., 2015) and ‘Corporate Responsibility and Sustainability’ (Camilleri, 2018), among others.

In sum, the proponents of these value-based theories sustain that there is a connection between the businesses’ laudable behaviors and their growth prospects. Currently, there are still a few contributions, albeit a few exceptions, that have focused their attention on the effects of stakeholder attributions on CSR and responsible environmental practices in the tourism and hospitality context.

This research confirmed that the CSR initiatives that are directed at internal stakeholders, like human resources, and/or environmentally friendly behaviors that can affect external stakeholders, including local communities are ultimately creating new markets, improving the companies’ profitability and strengthening their competitive positioning. Therefore, today’s businesses are encouraged to engage with a wide array of stakeholders to identify their demands and expectations. This way, they will be in a position to add value to their business, to society and the environment.

Managerial Implications

The strategic attributions of responsible corporate behaviors focus on exploiting opportunities that reconcile differing stakeholder demands. This study demonstrated that tourism and hospitality employers were connecting with multiple stakeholders. The respondents confirmed that they felt that their employers’ CSR and environmentally responsible practices were resulting in shared value opportunities for society and for the businesses themselves, as they led to an increased financial performance, in the long run.

In the past, CSR was associated with corporate philanthropy, contributions-in-kind toward social and environmental causes, environmental protection, employees’ engagement in community works, volunteerism and pro-bono service among other responsible initiatives. However, in this day and age, many companies are increasingly recognizing that there is a business case for CSR. Although, discretionary spending in CSR is usually driven by different stakeholders, businesses are realizing that there are strategic attributions, in addition to stakeholder attributions, to invest in CSR and environmental management practices (Camilleri, 2017a).

This contribution confirmed that stakeholder pressures were having direct and indirect effects on the businesses’ strategic outcomes. This research clearly indicated that both internal and external stakeholders were encouraging the tourism business to invest in environmentally friendly initiatives. This finding is consistent with other theoretical underpinnings (He, He & Xu, 2018; Graci & Dodds, 2008).

Recently, more hotels and restaurants are stepping in with their commitment for sustainability issues as they comply with non-governmental organizations’ regulatory tools such as process and performance-oriented standards relating to environmental protection, corporate governance, and the like (Camilleri, 2015).

Many governments are reinforcing their rules of law and directing businesses to follow their regulations as well as ethical principles of intergovernmental institutions. Yet, certain hospitality enterprises are still not always offering appropriate conditions of employment to their workers (Camilleri, 2021; Asimah, 2018; Janta et al., 2011; Poultson, 2009). The tourism industry is characterized by its seasonality issues and its low entry, insecure jobs.

Several hotels and restaurants would usually offer short-term employment prospects to newcomers to the labor market, including school leavers, individuals with poor qualifications and immigrants, among others (Harkinson et al., 2011). Typically, they recruit employees on a part-time basis and in temporary positions to economize on their wages. Very often, their low-level workers are not affiliated with trade unions. Therefore, they are not covered by collective agreements. As a result, hotel employees may be vulnerable to modern slavery conditions, as they are expected to work for longer than usual, in unsocial hours, during late evenings, night shifts, and in the weekends.

In this case, this research proved that tourism and hospitality employees appreciated their employers’ responsible HRM initiatives including the provision of training and development opportunities, the promotion of equal opportunities when hiring and promoting employees and suitable arrangements for their health and safety. Their employers’ responsible behaviors was having a significant effect on the strategic attributions to their business.

Hence, there is more to CSR than ‘doing well by doing good’. The respondents believed that businesses could increase their profits by engaging in responsible HRM and in ethical behaviors. They indicated that their employer was successful in attracting and retaining customers. This finding suggests that the company they worked for, had high credentials among their employees. The firms’ engagement with different stakeholders can result in an improved reputation and image. They will be in a better position to create economic value for their business if they meet and exceed their stakeholders’ expectations.

In sum, the objectives of this research were threefold. Firstly, the literature review has given an insight into mainstream responsible HRM initiatives, ethical principles and environmentally friendly investments. Secondly, its empirical research has contributed to knowledge by adding a tourism industry perspective in the existing theoretical underpinnings that are focused on strategic attributions and outcomes of corporate responsibility behaviors. Thirdly, it has outlined a model which clearly evidences how different stakeholder demands and expectations are having an effect on the businesses’ responsible activities.

On a lighter note, it suggests that Adam Smith’s ‘invisible hand’ is triggering businesses to create value to society whilst pursuing their own interest. Hence, corporate social and environmental practices can generate a virtuous circle of positive multiplier effects.

Therefore, there is scope for the businesses, including tourism and hospitality enterprises to communicate about their CSR and environmental initiatives through different marketing communications channels via traditional and interactive media. Ultimately, it is in their interest to promote their responsible behaviors through relevant messages that are clearly understood by different stakeholders.

Limitations and future research

This contribution raises awareness about the strategic attributions of CSR in the tourism and hospitality industry sectors. It clarified that CSR behaviors including ethical responsibility, responsible human resources management and environmental responsibility resulted in substantial benefits to a wide array of stakeholders and to the firm itself. Therefore, there is scope for other researchers to replicate this study in different contexts.

Future studies can incorporate other measures relating to the stakeholder theory. Alternatively, they can utilize other measures that may be drawn from the resource-based view theory, legitimacy theory or institutional theory, among others. Perhaps, further research may use qualitative research methods to delve into the individuals’ opinions and beliefs on strategic attributions of CSR and on environmentally-sound investments, including circular economy systems and renewable technologies.

You must be logged in to post a comment.