Featuring excerpts from one of my latest article focused on the intersection of ESG performance and the promotion of the sustainable tourism agenda – published through Business Strategy and the Environment:

Suggested citation: Camilleri, M.A. (2025). Environmental, social and governance (ESG) factors for sustainable tourism development: The way forward toward destination resilience and growth, Business Strategy and the Environment, https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/journal/10.1002/bse.70366

1 Introduction

Sustainable tourism is based on the principles of sustainable development (Fauzi 2025). It covers the complete tourism experience, including concerns related to economic, social and environmental issues (Bang-Ning et al. 2025; Wang and Zhang 2025). Its long-term dual objectives are to improve the tourists’ experiences of destinations they visit and to address the needs of host communities (Kim et al. 2024). Arguably, all forms of tourism have the potential to become sustainable if they are appropriately planned, led, organised and managed (Camilleri 2018). Destination marketers and tourism practitioners who pursue responsible tourism approaches ought to devote their attention to enhancing environmental protection within their territories, to mitigating the negative externalities of the tourism industry on the environment and society, to promoting fair and inclusive societies to enhance the quality of life of local residents, to facilitating exposure to diverse cultures, while fostering a resilient and dynamic economy that generates jobs and equitable growth for all (Rasoolimanesh et al. 2023; Scheyvens and Cheer 2022).

Conversely, irresponsible tourism practices can lead to the degradation of natural habitats, greenhouse gas emissions and the loss of biodiversity through air and water pollution from unsustainable transportation options, overconsumption of resources, waste generation and excessive construction (Banga et al. 2022; H. Wu et al. 2024). Indeed, any nation’s overdependence on tourism may give rise to economic difficulties during economic crises, such as increased cost of living for residents, seasonal income and precarious employment conditions, leakage of revenues when profits go to foreign-owned businesses and displacement of traditional industries like fishing and agriculture, among other contingent issues (Mtapuri et al. 2022; Mtapuri et al. 2024).

In addition, tourism may trigger social and cultural externalities like overcrowding and an increased strain on public services, occupational hazards for tourism employees and inequalities due to uneven distribution of benefits, displacement of local communities to give way to tourism infrastructures, the loss of authenticity in local traditions, an erosion of local identities and traditional lifestyles under external influence, as well as increased crime rates or illicit activities (Ramkissoon 2023).

In light of these challenges, this research seeks to provide a better understanding of how environmental, social and governance (ESG) dimensions can be embedded within sustainable tourism, to strengthen long-term destination resilience and economic growth. Debatably, although the use of the ESG dimensions is gaining traction in various corporate suites, their application in tourism and hospitality industry contexts is still limited. Notwithstanding, ESG research is still suffering from inconsistent conceptualisations, measurements and reporting systems (Legendre et al. 2024).

To address this gap, this contribution outlines five interrelated objectives: (1) It relies on a systematic review methodology to investigate the intersection of ESG principles and sustainable tourism; (2) It synthesises the findings and maps thematic connections related to environmental stewardship, social equity and governance structures in tourism destinations; (3) It evaluates ESG-based strategies that address carrying capacity limitations, overtourism, climate vulnerabilities, sociocultural tensions and institutional accountabilities; (4) It advances theoretical insights; and (5) It develops a comprehensive conceptual framework, to guide policymakers, practitioners and stakeholders in embedding ESG considerations into tourism planning and development, thereby promoting environmental sustainability, socioeconomic resilience and corporate governance.

Guided by these objectives, this timely research addresses four central research questions. Firstly, it asks: [RQ1] How have high-impact scholarly works conceptualised and operationalised ESG dimensions in order to promote sustainable travel destinations? Secondly, it seeks to answer this question: [RQ2] What empirical evidence exists on the effectiveness of ESG-aligned strategies in enhancing destination resilience and fostering long-term economic growth? The third question interrogates: [RQ3] What academic implications arise from this contribution, and how might its insights shape the future research agenda? Finally, the study seeks to address this question: [RQ4] How and in what ways are the ESG pillars interacting within sustainable tourism policy and practices? This research question recognises that the ESG dimensions may or may not always align harmoniously with the sustainable tourism agenda.

Although the sustainable tourism literature has often been linked to the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) and to broader corporate social responsibility (CSR) frameworks, the explicit integration of ESG principles into this field is still underdeveloped (Back 2024; Legendre et al. 2024; Lin et al. 2024; Shin et al. 2025). Much of the existing literature examines the environmental, social and governance (E, S and G) dimensions in isolation (Moss et al. 2024), with scholars often addressing, for example, environmental sustainability through climate adaptation strategies or governance via destination management systems, without adequately considering their interdependence or combined impact on tourism outcomes (Comite et al. 2025; Kim et al. 2024). This pattern was clearly evidenced in the findings of this research.

This article synthesises the findings of recent high-impact publications focused on sustainable tourism through the ESG performance lens, in order to advance a holistic conceptual model that bridges academic scholarship and policy application. In sum, this proposed theoretical framework clarifies how environmental stewardship, social inclusivity and governance accountability are shaping sustainable tourism trajectories. In conclusion, it puts forward original theoretical as well as the managerial implications. Theoretically, it enriches the sustainable tourism literature with an ESG-integrated analytical framework grounded in systematic evidence. Practically, it offers an actionable, governance-oriented blueprint that aligns environmental, social and economic objectives for responsible tourism planning and development. Hence, it provides a tangible roadmap that embeds ESG dimensions and their related criteria into sustainable tourism strategies for destination resilience and long-term competitiveness.

2 Background

The evolution of sustainable and responsible tourism paradigms can be traced back to the environmental consciousness that characterised the 1960s and 1970s. At the time, several governments were concerned over the ecological and cultural consequences of mass tourism. Early initiatives, such as the European Travel Commission’s 1973 campaign for environmentally sustainable tourism, sought to mitigate the negative externalities of rapid sector growth. Subsequently, South Africa’s 1996 national tourism policy introduced the concept of responsible tourism, that essentially emphasised community well-being as an integral component of destination management. The United Nations World Tourism Organization (UNWTO) has since positioned sustainable tourism as a catalyst for global development.

Eventually, the declaration of 2017 as the International Year of Sustainable Tourism for Development has underscored its potential to contribute directly to the United Nations SDGs. Specific targets like SDG 8 (decent work and economic growth), SDG 12 (responsible consumption and production), SDG 14 (life below water) and SDG 15 (life on land) highlight the sector’s capacity to create jobs, preserve ecosystems, safeguard cultural heritage and benefit vulnerable economies (Mahajan et al. 2024), particularly in small island states and least developed countries (Grilli et al. 2021). However, an ongoing achievement of these objectives necessitates balancing environmental, social and economic interests, a process that is often complicated by the diverse, and at times conflicting, priorities of a wide array of stakeholders (Civera et al. 2025).

Governments are important actors in this process. They can influence sustainable tourism outcomes through regulation, education, destination marketing and public–private partnerships (Dossou et al. 2023; Mdoda et al. 2024). Generally, their underlying policy rationale is to ensure that tourism development supports long-term economic growth while protecting cultural and natural assets, in order to improve community well-being (Andrade-Suárez and Caamaño-Franco 2020; Breiby et al. 2020). Yet this ambition is often undermined by market pressures, limited institutional capacities and the difficulty of translating high-level sustainability commitments into enforceable measures at the local levels.

In this light, the ESG framework a concept that was popularised by a United Nations Global Compact (2004) report, entitled, “Who Cares Wins”, offers a coherent approach for the integration of environmental stewardship, social equity and institutional accountability for the advancement of responsible tourism planning and development. Hence, in this context, practical tools are required in order to translate inconsistent guiding principles into actionable destination management strategies. For instance, the carrying capacity acts as a practical control mechanism within such a theoretical framework (Mtapuri et al. 2022; O’Reilly 1986). It ensures that tourism figures remain compatible with the preservation of natural, cultural and heritage assets. For the time being, there are challenges as well as opportunities for governments to translate the holistic vision of sustainable tourism policies into robust governance systems that maintain economic vitality and the integrity of their destinations.

4 Results

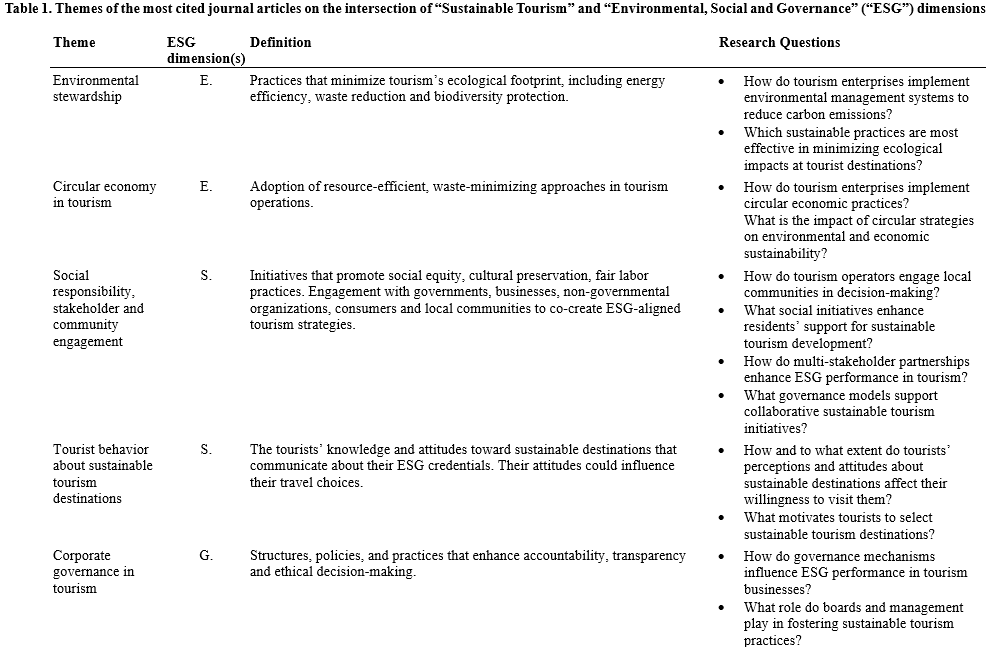

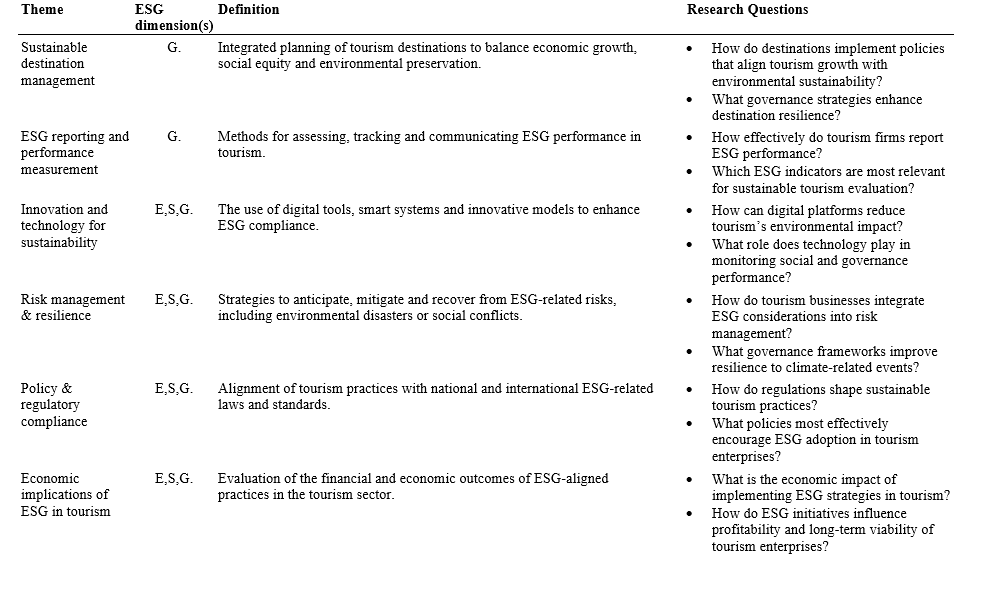

The thematic analysis indicates that the sustainable tourism concept is interconnected with each of the ESG’s dimensions. The findings suggest that sustainable tourism integrates environmental stewardship, social responsibility and sound governance to advance ecological preservation, community well-being and organisational accountability. Hence, it supports long-term destination resilience. The bibliographic results report that each of the ESG components is not only essential for sustainable tourism but also interdependent pillars that enable the sector to thrive in a responsible manner. Therefore, it is imperative for governments to safeguard natural and cultural heritage, empower local communities and foster transparent and effective governance, to ensure the sustainable development of destinations as well as their economic growth (Chong 2020; Grilli et al. 2021; Mamirkulova et al. 2020). The ESG framework, along with its criteria, serves as an important lens through which stakeholders can shape and evaluate sustainable tourism policies and practices (Işık, Islam, et al. 2025). Table 1 features the most conspicuous themes that emerged from this study. Additionally, it presents definitions for each theme along with illustrative research questions examined by the academic contributions identified in this systematic review.

4.1 The Environmental Dimension of Sustainable Tourism

The tourism industry is dependent on natural ecosystems. Therefore, it is in the tourism stakeholders’ interest to protect the environment and to minimise their externalities (J. S. Wu et al. 2021). There is scope for them to promote the conservation of land and water resources (Sørensen and Grindsted 2021). Water scarcity is a pressing global concern that is amplified in many tourist hotspots (WTTC 2023). However, tourism development and its related infrastructural expansion ought to respect ecological thresholds and preserve green spaces, particularly in urban areas. Hotels, resorts and attractions could implement water-saving technologies such as rainwater harvesting, low-flow fixtures and wastewater recycling (Foroughi et al. 2022). These sustainable measures reduce stress on local water supplies and help preserve aquatic ecosystems. In addition, tourism entities can avail themselves of renewable energy sources like solar panels, wind turbines, et cetera, and may adopt energy-efficient appliances and lighting solutions (Abdou et al. 2020; Zhan et al. 2021).

The rapid growth of tourism has historically been linked to environmental degradation through waste accumulation and pollution (Bekun et al. 2022). Circular economy strategies including improved waste management and pollution control through responsible waste disposal as well as reducing, reusing and recycling certain resources, can help decrease the industry’s externalities, but also create healthier spaces for tourists and staff (Camilleri 2025; Dey et al. 2025; Jain et al. 2024).

Tourism significantly contributes to the generation of greenhouse gas emissions through transportation and accommodation (Kim et al. 2024). Addressing climate change within sustainable tourism is critical to reducing the sector’s ecological footprint and enhancing destination resilience to climate impacts (Comite et al. 2025; Scott 2021). Many tourism businesses invest in carbon offset programs including reforestation, renewable energy projects and community-based conservation as mechanisms to offset their emissions (Banga et al. 2022). Eco-certifications such as Global Sustainable Tourism Council (GSTC), Green Globe, EarthCheck, GreenKey and LEED, among others, encourage the adoption of low-carbon practices. They enable practitioners and consumers to make environmentally conscious choices (Dube and Nhamo 2020; Gössling and Schweiggart 2022). Moreover, green transportation policies can encourage public transit, cycling, walking and the adoption of electric and hybrid vehicles for tourism-related travel, thereby reducing carbon footprints (Kim et al. 2024).

Ecologically sensitive zones such as national parks and marine reserves, which are home to wildlife, fragile species and habitats are some of the most visited places by tourists (Partelow and Nelson 2020; Tranter et al. 2022). Hence, they should be protected from overtourism by implementing visitor limits, buffer zones and conservation fees to reduce human impact (Leka et al. 2022). Restoration projects like reforestation, coral reef rehabilitation and wetland conservation are good examples of proactive environmental stewardship linked to tourism (Herrera-Franco et al. 2020; Muhammad et al. 2021). Environmental sustainability also depends on shaping tourist behaviours and fostering responsible activities like environmental awareness campaigns, community involvement in conservation efforts as well as engagement in low-impact alternatives like birdwatching, hiking and sustainable diving, among other stewardship practices (Khuadthong et al. 2025; J. S. Wu et al. 2021).

4.2 The Social Dimension of Sustainable Tourism

Sustainable tourism outcomes extend beyond environmental stewardship principles. Its social dimension encompasses criteria related to the preservation of cultural heritage; community engagement and empowerment; social equity, inclusion and cohesion; as well as responsible tourist behaviours, among other aspects (Bellato et al. 2023; Bianchi and de Man 2021; Joo et al. 2020a; Xu et al. 2020; Yang and Wong 2020; Rasoolimanesh et al. 2023). Sustainable tourism practices are clearly evidenced through improved relationships between tourists and local host communities, resulting in tangible benefits to both parties (Ramkissoon 2023).

The tourism industry can be considered a catalyst for cultural appreciation as well as a threat to cultural authenticity (Bai et al. 2024; H. Wu et al. 2024). Therefore, host destinations need to safeguard their cultural heritage, historical landmarks and monuments. Regulations and visitor management policies ought to be in place to limit wear and degradation of archaeological and religious sites, as well as historically important buildings and architectures (Mamirkulova et al. 2020). The social dimension of sustainable tourism entails that destination marketers preserve their cultural heritage and authenticity. They may do so by showcasing indigenous tastes and aromas of the region, including local foods and wines, and by promoting traditional music, dance, arts, crafts, et cetera, to appeal to international visitors (Andrade-Suárez and Caamaño-Franco 2020). This helps them keep their cultural legacy and maintain a competitive edge (Bellato et al. 2023). As a result, incoming tourists would be in a better position to appreciate local customs and folklore. Notwithstanding, their behaviours can play a crucial role in shaping social dynamics within destinations, as their activities might support community well-being and promote equitable access to tourism benefits (Mamirkulova et al. 2020).

However, policymakers are expected to manage visitor flows within a destination’s carrying capacity to prevent overcrowding, and to avoid social tensions, while fostering inclusivity, mutual respect and positive interactions between visitors and host communities (Back 2024; Koens et al. 2021). Perhaps, destination management organisations should educate visitors about cultural sensitivity issues to demonstrate their respect to host communities (Foroughi et al. 2022; Joo et al. 2020b; Mdoda et al. 2024). For example, they may raise awareness of appropriate behaviours in specific contexts, including dress codes and etiquette to mitigate cultural clashes, discourage exploitative tourism practices like invasive photography in certain settings and prevent unethical animal encounters, in order to foster mutual respect, enhance positive exchanges and safeguard community values (Ghaderi et al. 2024).

The sustainable tourism concept encourages participatory tourism planning. It prioritises the empowerment of indigenous communities in tourism decision-making and policy formulation (Ramkissoon 2023). The involvement of local residents may require capacity building to equip them with relevant skills to participate in the tourism sector, and to foster their economic advancement (Mamirkulova et al. 2020). The proponents of sustainable tourism frequently refer to the provision of fair employment opportunities, including for native populations, in terms of equitable wages and salaries, as well as decent working conditions, in order to enhance community livelihoods and social cohesion (Mtapuri, Camilleri, et al. 2022). Very often, they report that destinations would benefit from sustainable tourism practices that build social capital and reduce economic leakage, by incentivising local entrepreneurs and community-based tourism initiatives to ensure that financial returns remain within the community (Chong 2020; Partelow and Nelson 2020).

The systematic review postulates that the sustainable tourism concept is meant to promote social justice and reduce inequalities (Bianchi and de Man 2021). The extant research confirms that it fosters social inclusivity across various demographic groups in society by supporting gender equality, thereby enriching the sector’s diversity (Bellato et al. 2023; A. Khan et al. 2020). The industry’s labour market may include individuals hailing from different backgrounds in society, including young adults, women, senior citizens, immigrants and disabled people (Bianchi and de Man 2021; Camilleri et al. 2024). Tourism businesses are encouraged to develop infrastructures and services that accommodate people with accessibility requirements in order to broaden their destinations’ reach and social value (Sisto et al. 2022).

4.3 The Governance Dimension in Sustainable Tourism

The integration of environmental and social dimensions of sustainable tourism ultimately depends on transparent, accountable and participatory governance mechanisms (Joo et al. 2020b; Putzer and Posza 2024). Effective governance provides the institutional framework through which environmental stewardship and social responsibility are translated into actionable policies, coordinated initiatives and measurable outcomes (Back 2024; Ivars-Baidal et al. 2023).

Governments are entrusted to set the foundation for sustainable tourism through national and local tourism policies that clearly define sustainability goals, action plans and regulatory measures (Gössling and Schweiggart 2022). Such policies may be related to environmental and/or social regulations. They may enforce environmental impact assessments (EIAs), zoning laws and they could be meant to protect cultural heritage (Farsari 2023). Moreover, they may be intended to encourage or incentivise environmental sustainability practices (e.g., through eco-label or certification schemes) (Bekun et al. 2022). Alternatively, they may be focused on the destinations’ carrying capacity limits and/or on their overtourism aspects, if they specify visitor limits, and/or refer to taxes, levies or fees imposed on visitors or tourists (Leka et al. 2022).

Sustainable tourism governance depends on multisector cooperation (Farsari 2023) that may usually involve government departments and agencies, the private sector that may comprise accommodation service providers, airlines, tour operators, travel agencies as well as local communities, NGOs and international organisations, among others. Policymakers need to balance diverse stakeholders’ interests and to instil their shared responsibilities (Siakwah et al. 2020). Good governance can ultimately ensure that public–private partnerships would translate to long-term, sustainable tourism strategies related to responsible planning and development that consider specific socioenvironmental aspects of destinations: green building standards and the use of renewable energy, and/or emergency and crisis management issues (Scheyvens and Cheer 2022).

Policymakers are expected to conduct regular assessments and evaluations of tourism practitioners’ environmental, social and economic outcomes operating in their jurisdictions. They need to scrutinise corporate ESG disclosures, particularly in certain domains (e.g., in European contexts, where they ratified the corporate sustainability reporting directive) (Camilleri 2025). Governments should monitor business practices to safeguard their employees’ well-being, environmental sustainability and the communities’ interests (Putzer and Posza 2024). They may avail themselves of sustainability indicators and benchmarking tools such as GSTC’s criteria that are used to measure progress in sustainable tourism, in terms of sustainable management (planning, monitoring, governance); socioeconomic benefits to the local community, cultural heritage preservation and environmental protection (Wang and Zhang 2025). Such responsible and ethical practices increase trust and lead to continuous improvements in the tourism industry.

Discussion

The holistic integration of environmental, social and governance dimensions in sustainable tourism collectively contributes to enhance destination resilience and sustainable economic growth. The conservation of natural attractions such as beaches, forests and coral reefs will enable destinations to remain competitive. Therefore, there is scope in implementing climate-friendly measures, including reforestation and sustainable water management, among others, to reduce vulnerability to floods and storms. At the same time, they may curb ocean-level increases. Pollution prevention, waste minimization and circular economy strategies can help destinations maintain environmental quality, that is crucial for their ongoing tourism appeal. Notwithstanding, eco-certifications of responsible destinations can attract environmentally conscious travelers, who may be willing to pay more to visit sustainable tourism destinations.

The effectiveness of eco-certifications is amplified when combined with socially responsible practices. The integration of community empowerment, cultural heritage preservation, and social inclusiveness into tourism planning and development can contribute to increasing the sustainability of a destination. Hence, the tourism industry could add value to the environment as well as to local communities. By aligning sustainable development with local priorities and by promoting responsible tourism practices, destinations can provide authentic cultural and heritage experiences, thereby enhancing their visitor satisfaction and revisit intentions, in the future. In turn, this reinforces both market differentiation and long-term social resilience. Furthermore, as entrepreneurship flourishes, the local communities would benefit from circulating incomes and reduced economic leakages. Such outcomes are conducive to tourism growth.

However, policymakers must implement effective tourism governance to ensure that these economic gains are sustainable. Transparent governance fosters trust among stakeholders and facilitate sustainable growth and competitiveness. By implementing strategic planning and regulations, local authorities can ensure that tourism development| does not overwhelm infrastructure or degrade natural and cultural assets. This creates a balanced environment where entrepreneurship and community benefits coexist with long-term destination resilience. Therefore, sound governance prevents over-tourism and unmanaged expansion, whilst protecting the destinations’ assets. Robust tourism governance frameworks foster stable policy environments, attract further investments and enable long-term planning. Additionally, strong crisis management capabilities can equip destinations to handle unforeseen circumstances including pandemics, natural disasters and economic shocks.

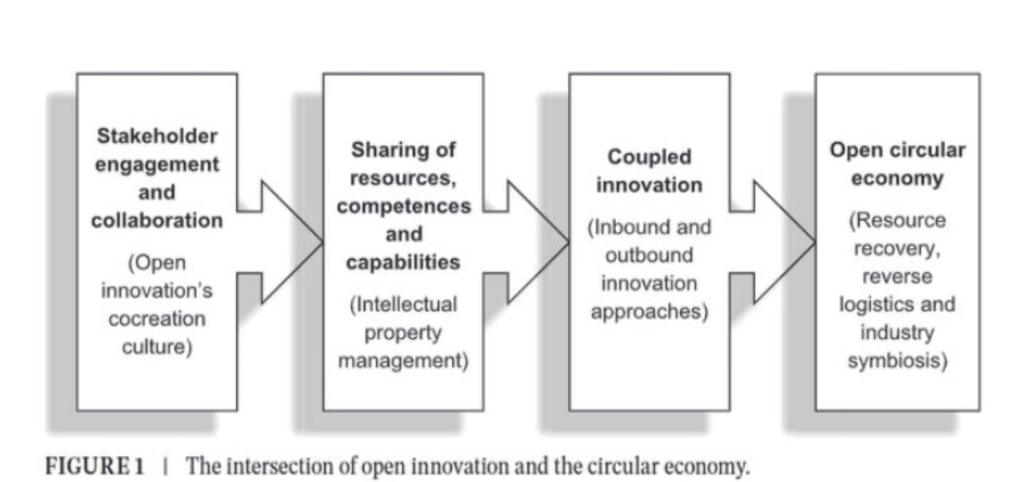

The above analysis underlines that environmental, social and governance dimensions are deeply interlinked to one another and mutually-reinforcing within sustainable tourism. An integrative ESG approach conceptualizes sustainable tourism as a synergistic framework that reconciles ecological integrity, social equity, and institutional effectiveness, as illustrated in Figure 1.

Theoretical implications

This study adds value to the growing body of literature focused on sustainable tourism governance (Gössling & Schweiggart, 2022; Işık et al., 2025; Rasoolimanesh et al., 2023). It clearly identifies key theoretical underpinnings of articles focused on the intersection of ESG dimensions and sustainable tourism practices. The bibliographic findings suggest that the stakeholder theory (Bellato et al., 2023; Ivars-Baidal et al., 2023; Matsali et al., 2025; Mdoda et al., 2024) and the institutional theory (Bekun et al., 2022; Dossou et al., 2023; Hall et al., 2020; Saarinen, 2021; Zhan et al., 2021) shed light on the role of government policies, corporate responsibility and community engagement in shaping the sustainable tourism agenda and different settings (Lin et al., 2024; Zhang et al., 2025). Interestingly, the Social Identity Theory clarifies how various stakeholder groups, including residents, tourists and industry practitioners, are aligning their behaviors with shared norms and identities that promote corporate ESG values (Yang & Wong, 2020). Drawing on Cognitive Appraisal Theory, it indicates that stakeholders’ evaluation of ESG-related risks and opportunities influences their emotional responses and subsequent engagement in sustainability initiatives (Foroughi et al., 2022). The Theory of Empowerment further explains how participatory governance and transparent decision-making can enhance community agency, fostering stronger local support for ESG-driven tourism strategies (Joo et al., 2020a).

In line with the Theory of Planned Behavior and the Attitude–Behavior–Context (ABC) Theory, the findings highlight that pro-sustainability intentions are by attitudes toward ESG as well as by perceived behavioral control and contextual enablers such as policy frameworks and market incentives (Joo et al., 2020b; Khuadthong et al., 2025; Wu et al., 2021). Moreover, the Value–Belief–Norm Theory demonstrates how environmental values and moral obligations underpin behavioral commitments to ESG-aligned tourism (Kim et al., 2024).

From a governance perspective, the Evolutionary Governance Theory clarifies how institutional arrangements, stakeholder relationships and regulatory norms adapt over time to embed ESG principles in tourism planning (Partelow & Nelson, 2020). The review suggests that tourism stakeholders’ decision-making including during uncertain situations, can be enriched through Decision Theory and by referring to the Interval-Valued Fermatean Fuzzy Set approach (Rani et al., 2022). These theories enable robust, data-informed prioritization of ESG objectives.

Furthermore, the findings underscore the recursive relationship between the human agency and the structural constraints. The results suggest that stakeholder actions can influence ESG governance systems. This argumentation is congruent with the Structuration Theory (Saarinen, 2021). Meanwhile, the Resource-Based View (Wang & Zhang, 2025; Zhu et al., 2021) and Dynamic Capabilities Theory (Wang & Zhang, 2025) frame ESG adoption as a strategic asset, where unique sustainability capabilities can enhance competitive advantage and long-term destination resilience.

Managerial implications

This research yields clear implications for policymakers, industry practitioners and local communities of tourist destinations. It postulates that the ESG dimensions can provide these stakeholders with a strategic framework to balance growth with long-term resilience. It confirms that ESG policies necessitate a comprehensive approach, that combines environmental conservation, social inclusion, and responsible governance considerations, rather than addressing them individually. Arguably, there may be variations in the importance, focus and implementation of ESG dimensions in tourism, in different contexts, due to the host countries’ economic capacities regulatory frameworks, social priorities and/or environmental challenges. As a result, the effects or outcomes of ESG initiatives are not uniform across destinations (Lin et al., 2024).

In addition, the size of the businesses can also influence their commitment to account and disclose ESG-related aspects of their performance. Large multinational travel and hospitality firms could benefit from economies of scale, in terms of greater financial, human, and technological resources, resulting in their ESG alignment and compliance with societal norms and regulatory frameworks. They can afford dedicated sustainability teams, advanced data management tools, and external consultants to ensure accurate measurement, benchmarking and disclosure of ESG performance. In stark contrast, the smaller firms may face resource constraints, limited expertise, and higher relative costs for data collection and reporting. Such non-commercial activities can hinder their ability to systematically track, measure and communicate ESG performance, placing them at a comparative disadvantage, relative to their larger counterparts.

From an environmental perspective, policy makers should operationalize carrying capacity thresholds and implement adaptive management systems to safeguard ecosystems, optimize resource utilization, and enhance climate resilience. Continuous monitoring and evaluation of environmental impacts are essential to ensure that tourism activities remain within sustainable limits. Proactive interventions including the promotion of low-carbon transportation, the adoption of renewable energy, efficient resource management, and waste reduction are critical for aligning tourism development with ESG objectives. Such strategies preserve biodiversity and can contribute to the long-term sustainability of destinations.

The social dimension emphasizes the equitable distribution of tourism benefits and the preservation of cultural integrity. Overtourism threatens community well-being through inflated living costs, cultural commodification and resident–visitor tensions. Hence, managers should foster participatory governance structures that empower local communities, entrepreneurs and cultural custodians in decision-making processes. Technological innovations including artificial intelligence (AI) solutions that monitor visitor flows can further support socially responsible destination management. At the same time, stakeholder engagement ensures that tourism operations retain their legitimacy in society.

Robust governance mechanisms underpin these strategies. Practitioners can align policies with international sustainability standards in order to facilitate transparent accountability. The implementation of ESG performance indicators, enforceable visitor limits and adaptive regulatory measures, such as dynamic pricing or quotas enable evidence-based decision-making and continuous improvements in responsible destinations. The strengthening of institutional capacities and local skills ensures that governance frameworks are effective and sustainable over time.

Financial innovation is essential for sustainable tourism development. Policy makers ought to invest in green technologies and infrastructures to protect the natural environment from externalities. They can provide incentives and funds to support practitioners in their transition to long-term sustainability. By embedding ESG principles, destinations are in a better position to enhance their resilience to environmental and social shocks, strengthen their reputation and image, whilst maintaining their competitiveness in the global tourism market.

Policymakers are encouraged to increase their enforcement of regulations to trigger responsible behaviors. At the same time, they need to nurture relationships with stakeholders. The hoteliers should embed social innovations and environmentally sustainable practices into core strategies and operations. As for local communities, it is in their interest to actively participate in tourism planning and development, to ensure they preserve their cultural heritage and share tourism benefits in a fair manner. Collectively, this contribution’s integrated ESG approach positions destinations for sustained economic growth while safeguarding environmental and social well-being.

Conclusion

This article reinforces the significance of integrating ESG principles into sustainable tourism strategies. By addressing environmental concerns, fostering social inclusivity, improving governance frameworks, and ensuring economic viability, stakeholders can contribute to a more resilient and responsible tourism sector. This research demonstrates that sustainable tourism is most effectively achieved through the integration of environmental, social, and governance (ESG) dimensions, which together foster long-term destination resilience and economic growth. Environmentally, sustainable tourism requires the preservation of natural ecosystems, efficient resource use, and proactive measures to reduce pollution and greenhouse gas emissions. Practices such as water-saving technologies, renewable energy adoption, waste reduction, and circular economy strategies not only mitigate ecological impacts but also enhance the attractiveness and competitiveness of destinations.

From a social perspective, sustainable tourism supports community empowerment, cultural preservation, inclusivity, and social equity. By engaging local residents in planning and decision-making, promoting equitable employment, and safeguarding cultural heritage, destinations can foster positive resident–visitor interactions and enhance the overall visitor experience. Responsible tourist behavior, participatory governance, and cultural sensitivity further reinforce social cohesion while ensuring that tourism benefits are broadly shared within host communities.

Effective governance underpins both environmental and social outcomes by providing transparent, accountable, and coordinated frameworks for sustainable tourism. Policymakers and destination managers play a critical role in enforcing regulations, monitoring ESG performance, and balancing stakeholder interests. Multi-sector collaboration, the application of sustainability indicators, and adaptive management strategies enable destinations to anticipate and respond to environmental, social, and economic shocks.

Collectively, the ESG approach positions sustainable tourism as a synergistic model that aligns ecological integrity, social responsibility, and institutional effectiveness. By embedding ESG principles into core strategies, destinations can deliver unique, high-quality experiences, strengthen community livelihoods, and maintain global competitiveness. This integrative framework demonstrates that environmental stewardship, social equity, and sound governance are mutually reinforcing, offering a pathway for destinations to achieve enduring sustainability, resilient growth, and enhanced market differentiation.

The full paper is available here:

Open Access Repository @University of Malta: https://www.um.edu.mt/library/oar/handle/123456789/141666

You must be logged in to post a comment.