The following texts are excerpts from one of my latest articles.

Suggested Citation: Camilleri, M.A. & Camilleri, A.C. (2021). The Acceptance of Learning Management Systems and Video Conferencing Technologies: Lessons Learned from COVID-19, Technology, Knowledge and Learning, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10758-021-09561-y

Introduction

An unexpected Coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic has disrupted the provision of educational services in various contexts around the globe (Rahiem, 2020; Johnson, Veletsianos & Seaman, 2020; Bolumole, 2020). During the first wave of COVID-19, several educational institutions were suddenly expected to interrupt their face-to-face educational services. They had to adapt to an unprecedented situation. This latest development has resulted in both challenges and opportunities to students and educators (Howley, 2020; Araújo, de Lima, Cidade, Nobre, & Neto, 2020). Education service providers, including higher education institutions (HEIs) were required to follow their respective governments’ preventative social distancing measures and to increase their hygienic practices, to mitigate the spread of the pandemic. Several HEIs articulated contingency plans, disseminated information about the virus, trained their employees to work remotely, and organized virtual sessions with students or course participants.

Course instructors were expected to develop a new modus operandi to deliver their higher education services, in real time (Johnson et al., 2020). During the pandemic, many HEIs migrated from traditional and blended teaching approaches to fully virtual and remote course delivery. However, their shift to online, synchronous classes did not come naturally. COVID-19 has resulted in different problems to course instructors and to their students. In many cases, during the pandemic, educators were compelled to utilize online learning technologies to continue delivering their courses (Fitter, Raghunath, Cha, Sánchez, Takayama & Matarić, 2020). In the main, educators have embraced the dynamics of remote learning technologies to continue delivering educational services to students, amid peaks and troughs of COVID-19 cases.

Subsequently, policy makers have eased their restrictions when they noticed that there were lower contagion rates in their communities. After a few months of lockdown (or partial lock down) conditions, there were a number of HEIs that were allowed to open their doors. They instructed their visitors to wear masks, and to keep socially distant from each other. Most HEIs screened individuals for symptoms as they checked their temperatures and introduced strict hygienic practices like sanitization facilities in different parts of their campuses.

However, after a year and a half, since the outbreak of COVID-19, some academic members of staff were still relying on the use of remote learning technologies like learning management systems (like Moode) and video conferencing software to teach their courses (Cesco, Zara, De Toni, Lugli, Betta, Evans & Orzes, 2021). During the pandemic, they became acquainted with online technologies that facilitated asynchronous learning through text and/or recorded video (Sablić, Mirosavljević & Škugor, 2020). Moreover, many of them, organized interactive sessions with their students in real time. Very often, they utilized video conferencing platforms including Microsoft Teams, Google Meet, Zoom, D2L, Webex, Adobe Connect, Skype for Business, Big Blue Button and EduMeet, among others. COVID-19 has triggered them to use these remote technologies to engage in two-way communications with their students.

Although in the past year, there were a number of researchers who have published discursive articles about the impacts of COVID-19 on higher education, for the time being, there are just a few empirical studies on the subject (Bergdahl & Nouri, 2020; Aguilera-Hermida, 2020; Gonzalez, de la Rubia, Hincz, Comas-Lopez, Subirats, Fort & Sacha, 2020). This contribution addresses this gap in academia. Specifically, it investigates the facilitating conditions that can foster the students’ acceptance and usage of remote learning technologies. It examines the participants’ utilitarian motivations to utilize asynchronous learning resources to access course material, and sheds light on their willingness to engage with instructors and/or peers through synchronous, video conferencing software, to continue pursuing their educational programs from home, during an unexpected pandemic situation.

This study builds on previous theoretical underpinnings on technology adoption (Cheng & Yuen, 2018; Al-Rahmi, Alias, Othman, Marin & Tur, 2018; Merhi, 2015; Schoonenboom, 2014; Lin, Zimmer & Lee, 2013; Chen, Chen & Kazman, 2007; Ngai, Poon & Chan, 2007; Davis, 1989). At the same time, it explores the students’ perceptions about the interactivity (McMillan & Jang-Sun Hwang, 2002) of LMS as well as video conferencing software, and sheds light on their HEI’s facilitating conditions (Hoi, 2020; Dečman, 2015; Venkatesh, Thong & Xu, 2012; Venkatesh, Morris, Davis & Davis, 2003). The rationale of this study is to better understand the research participants’ intentions to use remote technologies, to improve their learning journey. To the best of our knowledge, there are no other contributions that have integrated the same measures that have been used in this research. Therefore, this study differentiates itself from the previous literature, and puts forward a research model that is empirically tested.

The development of remote learning

According to the social constructivist theory, individuals necessitate social interactions (Fridin, 2014; Lambropoulos, Faulkner & Culwin, 2012; Ainsworth, 2006; Tam, 2000). They develop their abilities by interacting with others. Therefore, online learning environments ought to be designed to support and challenge the students’ reflective and critical skills, by including interactive learning and collaborative approaches (Rienties & Toetenel, 2016; Dabbagh & Kitsantas, 2012; Wang, 2009; Wang, Woo, & Zhao, 2009). Social constructivism and discovery-based learning techniques emphasize the importance of having students who are actively involved in their learning process. This is in stark contrast with previous educational viewpoints where the responsibility rested with the instructor to teach, and where the learner played a passive, receptive role (Lambropoulos et al., 2012).

Today’s students are increasingly using online technologies to learn, both in and out of their higher educational institutions (Al-Maroof, Al-Qaysi, & Salloum, 2021). They are using interactive media to acquire formal and informal skills (Dabbagh & Kitsantas, 2012), particularly when they take part in constructivist activities with their peers and course instructors (Fridin, 2014). This argumentation is consistent with the collaborative learning theory (Lambropoulos et al., 2012; Khalifa & Kwok, 1999). Students can use digital technologies to access recorded podcasts (Merhi, 2015; Lin et al., 2013), watch videos (Hung, 2016) and interact together through live streaming technologies in real time (Payne, Keith, Schuetzler & Giboney, 2017). Hence, online education has fostered collaborative learning approaches (Wang, 2009). Computer mediated education enables students to search for solutions, to share online information with their peers, to evaluate each other’s ideas, and to monitor one another’s work (Lambić, 2016; Sung et al., 2015; Soflano, et al., 2015).

Course participants can use remote technologies, including their personal computers, smart phones and tablets to access their instructors’ asynchronous, online resources including course notes, power point presentations, videos clips, case studies, et cetera (Butler, Camilleri, Creed & Zutshi, 2021; Hung, 2016; Ifenthaler & Schweinbenz, 2013). Moreover, in this day and age, they are utilizing video conferencing technologies to attend virtual meetings, and to engage in one-to-one conversations, or in group discussions and debates with their course instructor and with other students. These virtual programs enable students to engage in synchronous communications with course instructors, to ask questions, and receive feedback, in real time.

A critical review of the relevant literature reported that university students were already using asynchronous technologies, in different contexts, before the outbreak of COVID-19 (Butler et al., 2021; Sánchez-Prieto et al., 2017; Hung, 2016; Liu et al., 2010; Sánchez & Hueros, 2010). Many authors held that online technologies were improving the students’ experiences (Crompton & Burke, 2018; Kurucay & Inan, 2017; Sánchez-Prieto et al., 2016). Before the outbreak of COVID-19, many practitioners blended traditional learning methodologies with digital and mobile applications to improve learning outcomes (Al-Maroof et al., 2021; Boelens et al., 2018; Furió et al., 2015). Course instructors can design and develop online learning environments to support their students with asynchronous resources (Wang et al., 2009). They may allow them to engage in collaborative learning activities through virtual environments (Rienties & Toetenel, 2016; Dabbagh & Kitsantas, 2012). These contemporary approaches are synonymous with the social constructivist theory (Fridin, 2014; Lambropoulos et al., 2012) and with discovery-based learning (Ifenthaler, 2012; Lambropoulos et al., 2012).

Theoretical implications

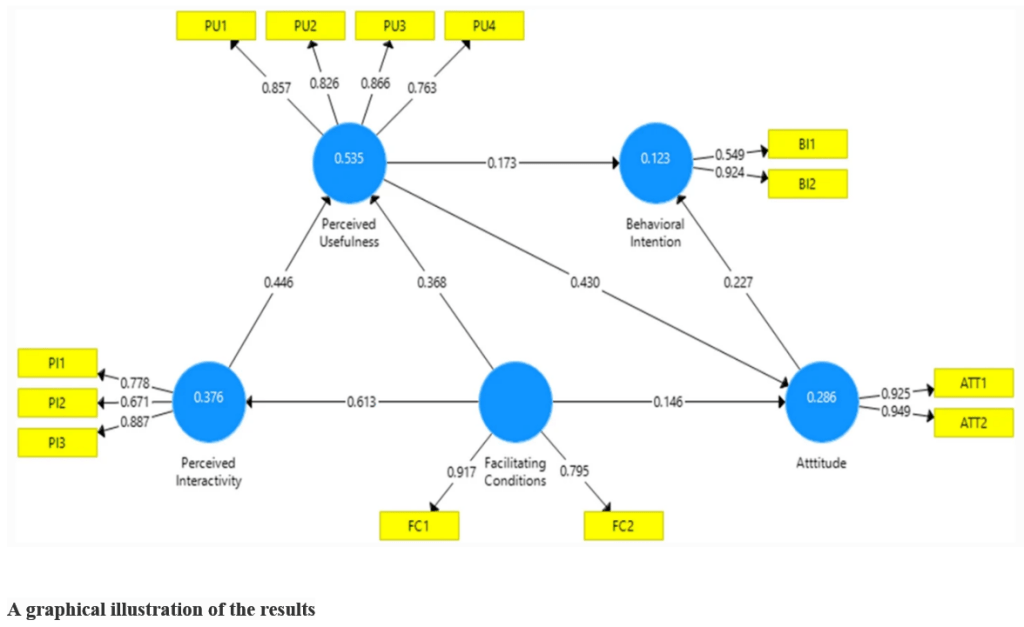

This contribution investigated the students’ perceived usefulness, perceived interactivity, attitudes toward use, facilitating conditions and behavioral intentions to utilize remote technologies. It posited that higher education students perceived the usefulness of remote learning technologies including LMS and video conferencing programs during COVID-19. The findings clearly indicated that they valued their interactive attributes. These factors have led them to embrace these programs during their learning journey. This study also confirmed that the universities’ facilitating conditions had a significant effect on their perceptions about the interactivity of these online learning resources and on their attitudes towards these technologies, as reported in Figure 1. This finding is consistent with previous research that reported that facilitating conditions is positively related to the students’ intentions to continue using digital and mobile learning resources (Gangwar et al., 2015; Teo, 2009).

This study has differentiated itself from previous contributions as it integrated facilitating conditions (Hoi, 2020; Dečman, 2015; Venkatesh et al. 2003; 2012) and perceived interactivity (Chattaraman et al., 2019; Chen et al., 2007; McMillan & Jang-Sun Hwang, 2002) with perceived usefulness (of technology) and attitudes (toward the use of technology) to better understand the students’ intentions to utilize remote learning technologies to improve their learning journey (Cheng & Yuen, 2018; Al-Rahmi et al., 2018; Merhi, 2015; Schoonenboom, 2014; Lin et al., 2013; Ngai et al., 2007; Davis, 1989) during an unexpected pandemic situation.

A bibliographic analysis revealed that there are a number of theoretical papers that have been published in the last eighteen months on this hot topic (Cesco et al., 2021; Fitter et al., 2020; Howley, 2020; Rahiem, 2020). Yet, to date, there are just a few rigorous studies, that examined the utilization of synchronous video conferencing technologies, in addition to conventional, asynchronous content, like LMS, in the context of higher education (Aguilera-Hermida, 2020; Gonzalez et al., 2020).

The findings from this research shed light on the utilitarian factors that were influencing the students’ engagement with interactive learning resources. According to the descriptive statistics, the students felt that remote technologies were useful to achieve their learning outcomes. They indicated that they were provided with appropriate facilitating conditions that enabled them to migrate to a fully virtual learning environment from face-to-face or blended learning approaches. During the pandemic’s lockdown or partial lockdown conditions, and even when the preventative measures were eased, many students were still using remote learning technologies to access online educational resources. They also kept using video conferencing technologies to attend to virtual classes, and to engage with their course instructor(s) and with their peers, in real time.

The confirmatory composite analysis reported that there were positive and highly significant effects that predicted the students’ intentions to use remote learning technologies. Evidently, educators have provided them with the necessary resources, knowledge and technical support to avail themselves of remote learning technologies. The respondents indicated that they accessed their course instructors’ online resources and regularly interacted with them through live conferencing facilities. The findings from SEM-PLS confirmed that the perceived usefulness and perceived interactivity with online technologies had a positive effect on their attitudes toward remote learning. This research implies that the students were confident with the utilization of interactive technologies to continue their educational programs. In fact, this research model proved that they were likely to use synchronous and asynchronous learning technologies in the foreseeable future, in a post COVID-19 context.

Implications of study for educators and policy makers

The COVID-19 pandemic and its preventative measures urged HEIs and other educational institutions to embrace video conferencing technologies to continue delivering student-centered education. This research suggests that educators ought to monitor their students’ engagement during their virtual sessions. It revealed that the students’ perceived interactivity as well as their higher education institutions’ facilitating conditions were having an effect on their perceptions about the usefulness of remote learning, on their attitudes as well as on their intentions to use them. These digital technologies were supporting the research participants in their learning journeys, whether they were at home or on campus. The students themselves perceived the usefulness of asynchronous LMS as well as of synchronous communications, including video conferencing software like Zoom or Microsoft Teams, among others.

These virtual technologies were already utilized in various contexts, before the outbreak of COVID-19. However, they turned out to be important learning resources in the realms of education. Course instructors are expected to support their students, by developing attractive digital learning resources (e.g. interactive presentations, online articles and recorded video clips) in appropriate formats that can be accessed with ease, through different media, including mobile technologies (Sablić et al., 2020). In this day and age, they can also use video conferencing technologies to interact with course participants in real time. When engaging with online resources, instructors should consider their students’ facilitating conditions, particularly if they are including high-res images, interactive media, including podcasts, videos, etc., in their LMSs. Their asynchronous content should be as clear and focused as possible, with links to relevant sources, including notes, case studies, quizzes, rubrics and formative assessments, among others.

COVID-19 has taught us that the individuals’ engagement with LMS and video conferencing software necessitate high‐quality wireless networks. There may be situations where students as well as their instructors may require online technical support, whether they are working from home of from university premises. Educational institutions including HEIs ought to regularly evaluate their students’ experiences with remote teaching in order to identify any issues that are affecting their academic performance (Camilleri, 2021b). HEI leaders are not always in a position to evaluate the quality and standards of their instructors’ online learning methods and to determine with absolute certainty whether their students have achieved their learning outcomes. During remote course delivery, students may not always have access to appropriate interactive technologies, learning materials or to adequate productive environments (Bao, 2020). There can be instances where course instructors and students could require facilitating conditions like technical support or training and development to enhance their competences and capabilities with the use of remote technologies.

A prepublication copy of this contribution can be downloaded through: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/353859136_The_Acceptance_of_Learning_Management_Systems_and_Video_Conferencing_Technologies_Lessons_Learned_from_COVID-19

You must be logged in to post a comment.